Exploration

Convoy Cowboys– Mapping maritime memories

Beneath the serene surface of the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Tunisia lies a largely forgotten chapter of history—an undersea landscape marked by the remnants of World War II convoy battles. These shipwrecks are silent witnesses to a vital yet often overlooked naval conflict that shaped the outcome of the North African campaign.

Text & photos by Jesper Kjøller.

Jesper Kjøller, editor-in-chief of Quest—Global Underwater Explorers’ member journal—chronicles the meticulous efforts to document and preserve these submerged sites, revealing their historical significance and honoring the men who risked everything to sustain the war effort. Through advanced underwater technology and dedicated research, ongoing projects uncover the enduring legacy of the Mediterranean convoys and the crucial role they played in the broader theatre of war.

The lovely deep blue color enveloping us as we descend is a hue found only in the heart of the Mediterranean. It’s almost midday, and the ocean above us completely flat, a perfect mirror reflecting nothing but sky. We have Bonaccia, the Italian term for dead calm.

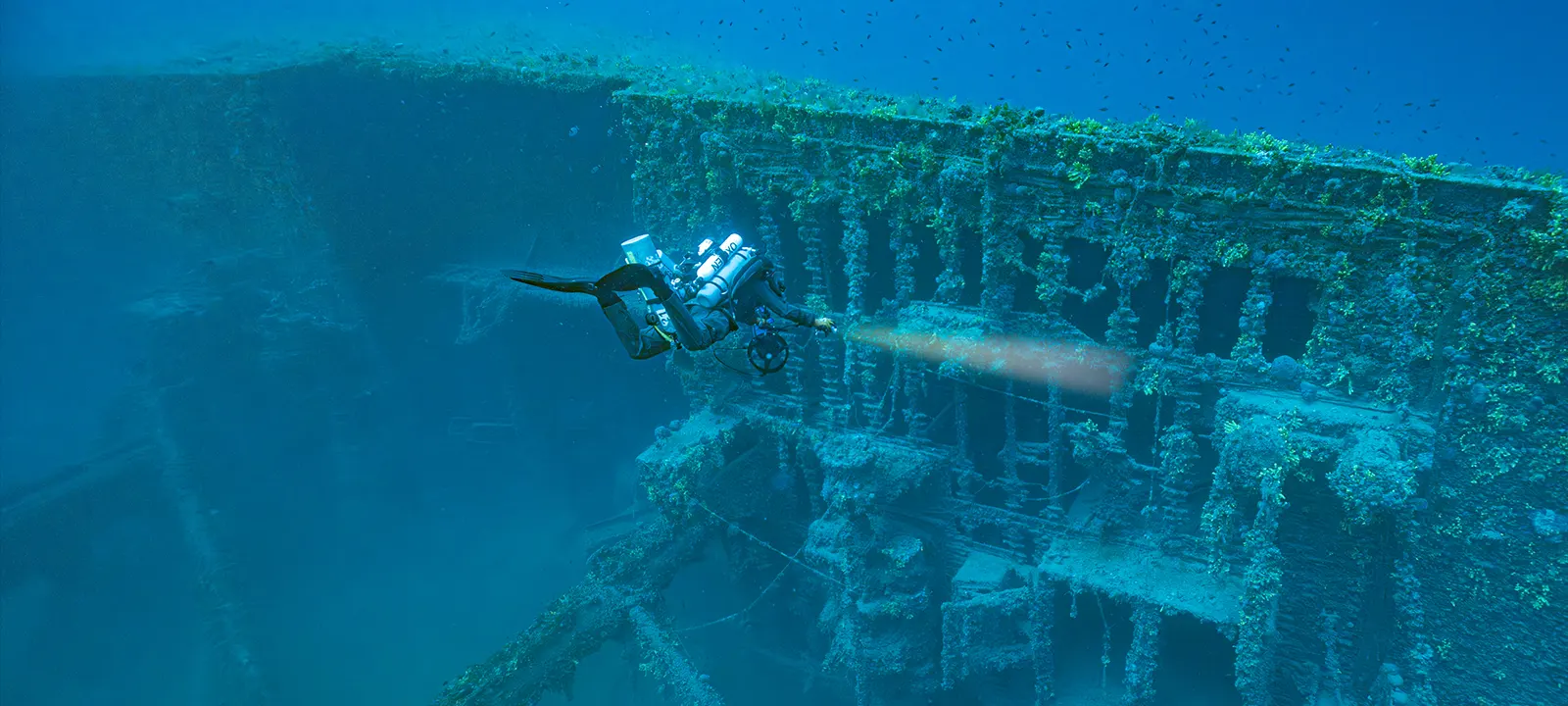

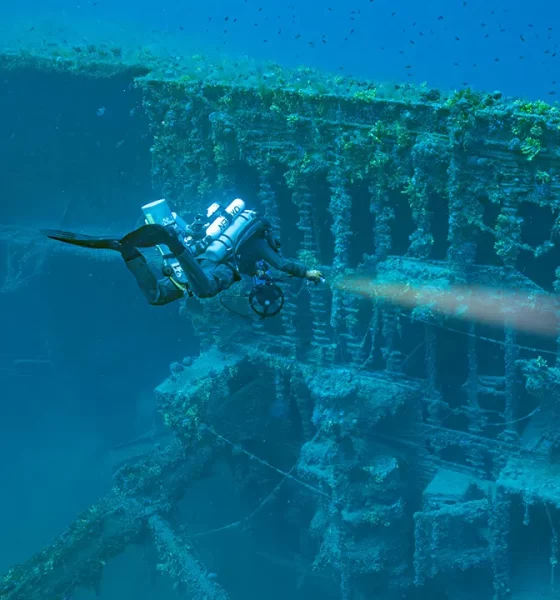

We follow the thin, white shot line with the attached ribbons every 3 m/10 ft to make it more visible. By the time we reach 30 m/110 ft, the shadow of the massive SS Beatrice begins to reveal itself beneath us. She rests on her port side, remarkably intact despite the years.

“The footage will feed the insatiable appetite of the photogrammetry model, slowly reconstructing the SS Beatrice in the digital realm.”

Stefano, Faisal and Thomas, who slipped beneath the surface 15 minutes before Rami and me, are already deeply immersed in their photogrammetry missions. Bright video lights fixed to their scooters pierce the twilight, casting glowing halos across the towering flanks of the sunken giant. The divers cruise alongside the wreck at staggered depths, maintaining precise distances as they methodically capture thousands upon thousands of high-resolution images—each frame a small piece of the puzzle. The footage will feed the insatiable appetite of the photogrammetry model, slowly reconstructing the SS Beatrice in the digital realm.

Below us, the seabed at 75 m/250 ft is a quiet chaos of debris, and scattered cargo—mute evidence of the moment SS Beatrice was claimed by the sea after an air raid in 1941.

Rami spots an intriguing cargo hold and steers his scooter toward the large, square opening—like a giant barn door hanging open to the sea. I follow him inside, and we begin exploring the vast interior, scattered with rusting fuel drums.

After 35 minutes on the bottom, we reluctantly begin our ascent after scootering the entire 137 m/450 ft from the bow to the stern. The long decompression ahead offers ample opportunity for my thoughts to drift back in time to the desert war that claimed this ship and the hundreds of others now lying silent in these waters.

The Desert Fox

The North African Campaign of World War II, famously marked by the rivalry between Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and General Bernard Montgomery, was one of the most demanding and strategically complex theaters of the war. Fought between 1940 and 1943 across the deserts of Libya and Egypt, the Desert War was a test of endurance, mechanized warfare, and above all, logistics.

The extreme environment made every movement equipment intensive. With open, featureless terrain, blistering heat, and fine sand that wreaked havoc on machinery, even basic operations became monumental tasks. Tanks, trucks, and artillery broke down regularly. There were no local resources to draw on—fuel, water, ammunition, and spare parts had to be shipped across dangerous waters.

For Rommel’s Axis forces, that meant relying on convoys sailing from Italy across the Mediterranean. But these convoys were relentlessly hunted by Allied forces based on the island of Malta. Submarines, bombers, and fast-attack craft decimated Axis shipping, causing chronic shortages. Rommel, AKA the Desert Fox frequently pushed ahead of his supply chain, leading to daring maneuvers that dazzled but often stalled due to a lack of fuel and ammunition.

The Allies, by contrast, had more stable supply routes via the Suez Canal and the port of Alexandria. Though not without challenges, their lines were longer-lasting and better protected. Montgomery’s leadership, beginning in 1942, brought a more methodical approach: no offensive began without a solid logistics base. This strategy paid off at the Second Battle of El Alamein, where Allied preparation and supply overwhelmed Rommel’s weakened Afrika Korps. It marked a turning point in the campaign.

Underreported naval war

Desert warfare, in many ways, resembled naval combat on land. Vast distances, minimal cover, and reliance on radio and reconnaissance gave battles a fluid, expansive character. Success depended on maneuver, coordination, and massing firepower at critical points—hallmarks of Montgomery’s patient yet powerful strategy.

Yet while tanks clashed in the desert, equally fierce battles raged at sea. Control of the Mediterranean was essential—whoever ruled the sea controlled the lifelines that kept desert armies alive.

Axis convoys sailed from Italian ports like Naples and Taranto to North African destinations such as Tripoli and Benghazi. Their mission was critical but perilous. Allied submarines and aircraft operating from Malta made the Central Mediterranean a deadly corridor. Fuel tankers and cargo ships were lost in alarming numbers, with each sinking reducing the Afrika Korps’ chances of survival.

To defend their supply lines, the Axis powers deployed warships and armed escorts. The Allies responded with daring naval engagements, surprise attacks, and stealth missions. Every ship that reached North Africa gave Rommel another chance; every loss brought him closer to collapse. These fierce engagements left behind a haunting legacy beneath the waves. Shipwrecks litter the seabed from Libya to Malta—silent remnants of a brutal, underreported naval war.

Control of the sea wasn’t a backdrop to the Desert War—it was its foundation. Without ships, there were no tanks, no food, no bullets. The desert victories depended on what happened at sea. And the wrecks that remain today—still bearing the scars of war—remind us that behind every land battle, there was a supply chain, a convoy, and a crew who risked everything to keep the war machine running.

While the majority of war supplies did reach the armies on land, both sides suffered significant losses in the process. The eventual success of the Allied forces in North Africa was due in large part to their vastly superior industrial capacity—especially that of the United States—which ensured a steady flow of men, equipment, and ammunition. This logistical advantage proved decisive. Furthermore, the German high command prioritized the Eastern Front, limiting the support available to Rommel’s Afrika Korps. This strategic decision, combined with overstretched supply lines and Allied control of the sea and air, contributed significantly to Rommel’s eventual defeat.

A game of Tetris

We’re diving from Granma 2, a 13-meter cabin cruiser—just large enough to support six divers—so the team is handpicked with that limit in mind. Six is an ideal number: flexible enough to split into two teams of three or three teams of two, depending on the day’s objective. The seventh member of the team is the heart of the operation—our skipper, cook, deckhand, and an exceptionally skilled CCR diver in his own right, Rocco Canella. His experience and calm presence are as essential as any piece of gear on board.

The boat is not initially designed for diving but with a few clever modifications, it does the job admirably. And compared to the assortment of fishing vessels used earlier in the project, it’s a clear upgrade. Still, with the sheer volume of equipment needed to support six CCR divers—cameras, scooters, bailout tanks, drysuits, undergarments and all the knickknacks of technical diving—it’s a constant game of Tetris to keep everything in order. We keep the chaos under control, and the boat is remarkably comfortable. What it lacks in space, it makes up for in flavor. Rocco and Stefano, unfazed by the cramped galley and limited provisions, spoil us daily with simple, delicious Italian meals. Their dishes—humble yet deeply satisfying—are a welcome comfort after long hours beneath the ocean.

The expedition follows an established template: Wait for a favorable two-day weather window, then depart at night so the 100-nautical-mile journey from Lampedusa to the wreck sites off the Tunisian coast can be completed while we sleep. Once on site, we typically complete two dives per day before returning to shore to refill tanks, resupply, and prepare for the next two-day run.

Gas management

Since we don’t have the capacity to refill tanks at sea, a slightly different protocol has been developed over the years. The twin-manifolded diluent tanks on the GUE-configured JJ-CCR units remain untouched during the dives. Instead, we feed the rebreather diluent from side-slung S40s routed through a switch block. In the event of a failure or if the drive gas runs low, it’s easy to switch to the onboard diluent, which is also accessible through the open-circuit regulators connected to the back-mounted tanks.

To preserve drive gas, we also use what’s commonly referred to as a fourth bottle. This is mounted opposite the oxygen tank and contains air for inflating both wing and drysuit. In a standard configuration, the wing is inflated via the right post of the back gas, and the suit from a separate inflation bottle, thus providing redundant buoyancy. However, inflating wings with precious trimix is a waste. But using the fourth bottle as the sole gas source for both inflation systems carries a significant risk—if that supply fails, the capacity to adjust buoyancy is completely lost. To mitigate this, we keep a backup inflation hose from the right post as a safeguard. But in an emergency, replacing the inflator hose under stress can be challenging. To address this, a dedicated switch block has been developed to simplify the process and enhance safety.

The project

Launched by SDSS (Società per la Documentazione di Siti Sommersi or the Society for the Documentation of Submerged Sites) in the early 2000s, this ongoing project documents aircraft and naval wrecks linked to the WWII Battle of the Mediterranean Convoys. Its mission is to use the intrigue of these underwater sites to tell the human stories behind them—reviving a lesser-known chapter of history and honoring the tens of thousands from many nations who fought, suffered, and died.

These remote wrecks are extraordinary pieces of historical heritage. SDSS sees documentation as a crucial first step toward protection, ensuring natural decay isn’t worsened by human activity. In Sicily and its surrounding islands, this work is carried out with the support of the Sicilian Region’s Superintendence of the Sea and the Museum of the Sea in Palermo.

Local fishermen from Lampedusa, Sicily, and Tunisia have been vital partners. While often unaware of the wrecks’ identities, their knowledge of the seafloor—where fishing nets snag or marine life gathers—has been key in locating the wreck sites.

GUE Instructor Mario Arena is one of the driving forces behind the project. He is a passionate underwater explorer and historian whose knowledge of the region, tireless curiosity, and deep respect for maritime history have helped transform scattered wrecks into compelling historical narratives. Through his leadership—and in collaboration with public institutions—the project has become far more than a research initiative. It now generates exhibitions, educational programs, digital archives, and immersive experiences that bring history to life.

Mario is especially passionate about three long-term goals. The first is increasing public awareness in Italy, particularly by integrating this largely underexposed piece of history into schools and educational curricula. The second is facilitating the development of a sustainable dive tourism industry in Tunisia, where many of the wrecks lie within reach and could form the foundation of a culturally rich and economically valuable heritage tourism sector.

The third goal focuses on creating awareness of a looming environmental threat beneath the waves—millions of gallons of fuel trapped in these wrecks will eventually leak as their tanks deteriorate, posing a serious ecological risk.

“The expedition follows an established template: wait for a favorable two-day weather window, then depart at night so the 100-nautical-mile journey from Lampedusa to the wreck sites off the Tunisian coast can be completed while we sleep.”

Keeping the stories alive

Being part of this project has been both a meaningful experience and a rare opportunity to connect with the history hidden beneath the waves—to honor the lives entwined with these wrecks. I’m grateful to contribute to the preservation of this maritime legacy and look forward to returning to continue this important work alongside others equally committed to the cause.

Sharing these stories with a wider audience is not only a privilege but a responsibility—to keep the legacy alive and to inspire others to value and protect this extraordinary underwater heritage. Through exploration and storytelling, we help ensure that the sacrifices of the convoy crews and the lessons of the past are never forgotten.

Fact File: Lampedusa

- Lampedusa is the largest of the Pelagie Islands, located in the Mediterranean Sea roughly midway between Sicily and the North African coast. It is part of Italy’s Sicily region but lies much closer to Tunisia than to mainland Italy. This strategic position has shaped Lampedusa’s history, culture, and modern significance.

- The island covers about 20 square kilometers and hosts a population of approximately 6,000 residents. The community is small but diverse, consisting largely of locals whose livelihoods have historically depended on fishing and agriculture. Over time, the economy has shifted significantly towards tourism, which now plays a central role. The Island is primarily frequented by Italian tourists, with very few international visitors. The island’s population experiences seasonal fluctuations, with numbers swelling in the summer months when guests arrive.

- Historically, Lampedusa’s location made it a strategic military point, especially during World War II. The island was occupied by Allied forces in 1943 as part of the campaign to control Mediterranean Sea routes and the southern approaches to Italy. Before and during the war, Lampedusa’s proximity to North Africa meant it was a key observation and staging post for naval and air operations. Though the island itself saw limited combat, it served as a vital link in the logistics chain and as a refuge for ships and aircraft.

- Today, remnants of wartime infrastructure such as bunkers and observation posts remain scattered across the island, offering tangible reminders of its strategic role during that global conflict. In recent decades, Lampedusa has also become known as a major landing point for migrants crossing from North Africa to Europe, highlighting its ongoing geopolitical importance and humanitarian challenges.

Resources include sdss.blue and underwaterhistory.org, with special thanks to Pelagos 2.0 Diving Center Lampedusa (www.pelagoslampedusa.it). The team consists of Mario Arena from Italy, Faisal Khalaf from Lebanon/Egypt, Stefano Gualtieri from Italy, Thomas Solberg from Norway, Rami Shakarchi from Switzerland/UAE, Jesper Kjøller from Denmark/UAE, and Rocco Canella from Italy.

Enjoyed this read? Here are more stories that tie into it.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Meet The British Underground by Michael Thomas (2020)

InDEPTH: From GUE’s membership magazine QUEST “British Cave Diving: Wookey Hole and The Cave Diving Group” by Duncan Price

InDEPTH: Exploring and documenting sa Conca ‘e Locoli cave 2021 by Andrea Marassich (2021)

Jesper Kjøller began his professional life as a musician but discovered his passion for diving over 30 years ago. He changed careers, becoming a diving instructor in 1994 and a PADI Course Director in 1999—the same year he took on the role of editor for the Scandinavian diving magazine DYK. He became a GUE instructor in 2011, and in 2015, relocated to Dubai to bring his talent for underwater storytelling and imagery to Deep Dive Dubai as the facility’s Marketing Manager. From his base in Dubai, Jesper travels the globe to teach, contribute to international dive publications, and take part in exploration projects such as the Mars field studies in the Baltic Sea, deep wreck exploration in UAE and Egypt, or the Battle of the Convoys project in the Southern Med. In 2021, he became Editor-in-Chief of Quest, GUE’s member journal.