Latest Features

Considerations When Buying a DPV

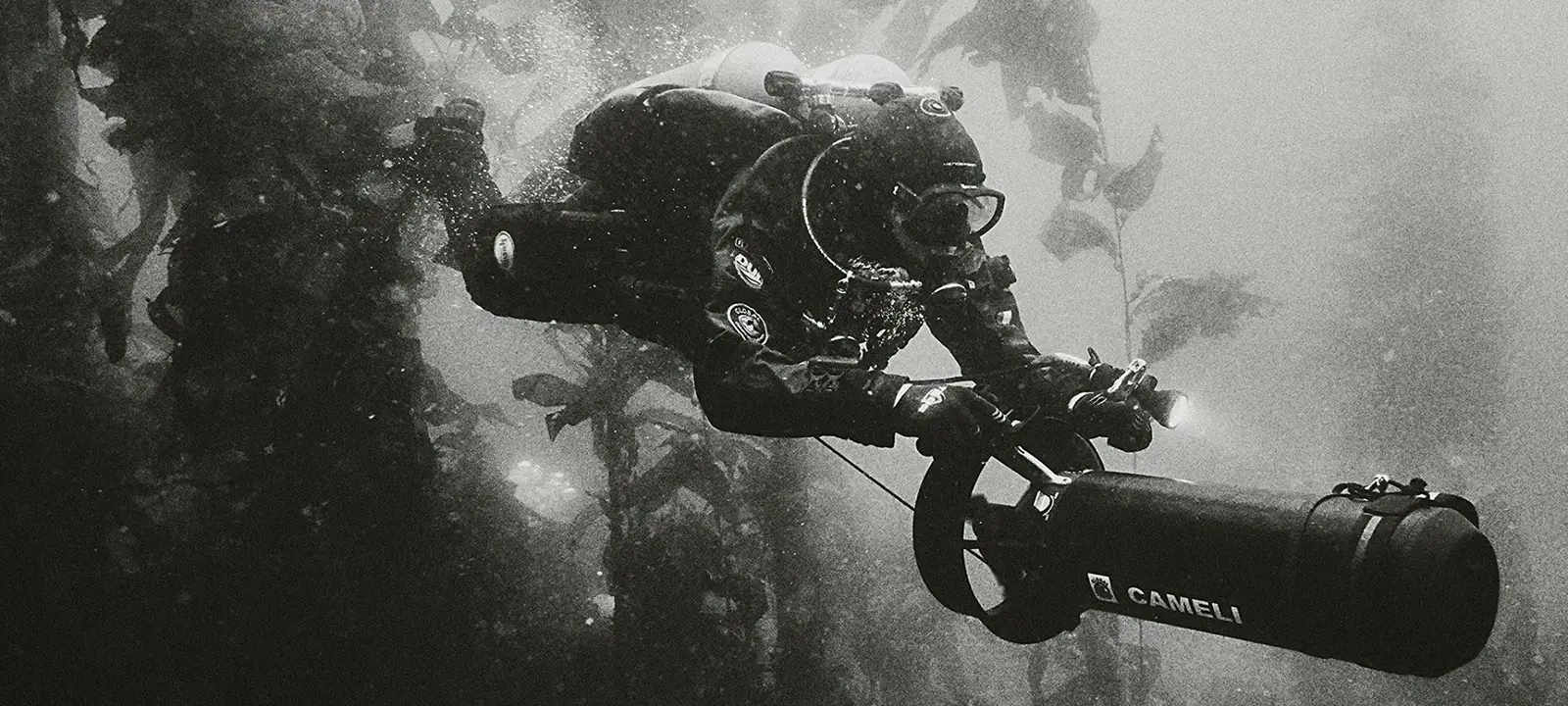

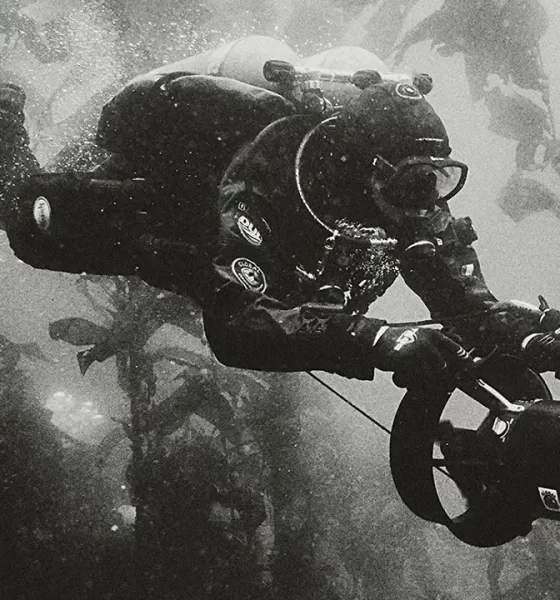

Diver propulsion vehicles (DPVs) have become increasingly important in tech diving for a variety of reasons. Here instructor DPV Francesco Cameli reviews the various aspects and features that you should consider in selecting a DPV. Dive in the fast lane?

By Francesco Cameli. Lead image : the author scootering offshore Catalina Island. Photo by Damon Loble.

I am a GUE instructor. As part of my curricula, I teach people to use diver propulsion vehicles (DPVs) safely and to have fun doing so. As a result, I have had the opportunity to see and try lots of different brands and models. What I have noticed is that sometimes students will purchase a particular DPV for the wrong reasons. So, I wanted to pose some questions and get you thinking about just what you might consider when choosing your unit. I do not wish to influence your choice of brand, nor will I single any one; instead, I’ll pose some considerations with a few pointers to help you make the right choice for you.

A few years ago, two divers in my local community put together an InDEPTH article that compared all the performance specs of the DPVs available at the time. This is a great resource and can be found here, Shop ‘Til You Drop: Comparing Tech DPVs. However, what I want to discuss are not specs at all but rather real life and use aspects of DPV selection and ownership.

So, what is a Diver Propulsion Vehicle? Is it a toy, is it fun, is it a tool? My personal opinion is that it is a tool and can be a lot of fun, but it has some drawbacks. Let us examine some pros and cons of DPV ownership and use.

First the pros:

They are fun!

Recent technologies have brought some much more affordable models to the table.

They allow you to get further on your dive.

They allow you to carry more gear with less effort.

They enable you to reach your intended target faster.

You can conserve gas by reducing your swimming work on the dive.

You produce less CO2 due to reduced workload.

They can help you mitigate a current (though you should not rely on them to do so).

They can make a very stable platform for cameras.

That’s a pretty good list; but how about the cons?

They can be costly.

They increase task-loading.

They allow you to get further on your dive. (So, further from home.)

You can get lost or separated from your team faster.

They allow your manual propulsion technique to deteriorate if used all the time.

They are electromechanical (so they can fail).

They can destroy the environment or visibility if used improperly.

They can injure you or a teammate if used incorrectly.

They can cause accidental loss of gas due to unnoticed free flows.

They can cause equalisation issues with ears, suits, BCDs, and counter lungs.

This is by no means an exhaustive list, but hopefully I’ve illustrated that there is more to the DPV than might immediately meet the eye.

A Wide Price Range

Let us then consider some factors that I feel you should consider when purchasing a DPV.

They come in all sorts of shapes and sizes! You can pick up a small handheld DPV for a few hundred bucks; but in this exploration, I would like to concentrate more on tow-behind DPVs—the most common variety found in the diving community.

On the smaller end of the spectrum, we had the Dive Xtras Piranha—small but scalable. It appears that these have been discontinued, so that leaves us with the smallest of the Dive Xtras BlackTips and the Seacraft Go (the latter having some serious specs considering its small size). Then we get to the mid-sized machines such as the Seacraft Ghost or Future, The Genesis, the Suex XJ Goldfinder, and several more to end up at the larger units such as the Suex XK Goldfinder. Does size matter? Well, that very much depends on what you plan to do with it.

Let’s talk about a large consideration for most: price. With units ranging from under $2,000 to over $11,000, budget is a factor. Here, there is no right or wrong; it’s more a matter of how much you are prepared to invest in your unit with mid-to high-price units usually holding their value over time. So, set your budget and go to town. With my own units, I took the approach of “Cry once and then look after your investment.” Without fail, I have always achieved good resale prices when I have chosen to upgrade or crossgrade.

Other huge considerations for me are reliability, build quality, and worldwide part availability for a unit. Not all DPVs are created equal and, sadly, I’ve found that even some of the most expensive units lack build quality. So, when I chose my units, I looked at overall resistance to abuse; shape, size, and material choices of various components—as well as whether the product felt solid and well-built when in hand. How does the trigger feel, how is it built, how are the switches, what is the body made of? The list of considerations goes on—which will ultimately come down to your personal preference, but be diligent in your examination of your contenders. Don’t just buy a “Brand X” because you hear it’s good. These are expensive tools; make up your own mind. I have owned a few high-value units and, in the end, my current units are head and shoulders above the rest when it comes to what I described in the above paragraph. Do what seems right for you.

Range and Speed

Notice that I’ve not yet mentioned range and speed. In my opinion, whatever unit we choose, those criteria should be further down the priority list. Here’s why:

Speed, to me, is an unnecessary metric; all DPVs propel you and, if you are using your units responsibly, you will be travelling at the speed of the slowest team member anyway. So, the fact that my top speed may blitz yours is less relevant. (Unless you find yourself on a project dive where speed is deemed to be important.)

Technique also plays a part in how fast you can go. I’ve seen divers with slower DPVs go faster than folks with a unit that, on paper, is faster. Why? Because they had better form while driving their units.

So, these top speeds that are in marketing materials are inaccurate metrics.

Also—for the gents in particular—full speed on a very fast DPV is somewhat bothersome on the old family jewels. There are harnesses and DPV sticks, but now you need yet more gear!

Also of note: The faster you go, the more you miss on a dive. You simply don’t have the time to take it all in. So, for me, if my unit does not crawl, top speed is a lower priority.

What about burn time? With battery technology getting better and better, the burn times are getting longer and longer. But here’s the thing: Unless you are going on some seriously long exploration dives (which, let’s face it, most of us are not) or you are on a long cave dive where you would need a backup DPV anyway, I cannot remember the last time I ever got anywhere near maxing out my battery life on a day of diving. Fair to say that I use higher-end units, but I’m still not even close to running out of burn time (particularly in the ocean). Here, too, we run into some issues with printed marketing material. Often, they state “X minutes at cruising speed,” but that leaves out how loaded a diver is and how proficient the diver is at riding a unit, making that metric also unreliable in my opinion.

Basically, all the higher-end DPVs have more than enough range for anyone but the most adventurous of divers.

Along the same line, much debate is heard in the community between brushless or brushed motors. I’ve had both and both worked flawlessly. In the end, one simple thing led me to my choice: To date, I have not found a brushless motor-equipped DPV where the power is applied instantly when I pull the trigger. I find that particularly irritating. When it’s time to go, I want to go and not wait for some electronics to figure out how to ramp up a brushless motor. Even with the ramp-up set to the fastest speed on a rather nice DPV I recently sold, it felt like an eternity.

If I’m teaching a DPV class and I need to chase a student, I need that power instantly (and full power instantly, too). With my old DPV, it took two clicks to get going followed by another two clicks on the second trigger to get full power. On my current unit, I just press the trigger to the appropriate position and the thing just takes off. That ultimately helped me make my decision.

Some like that brushless motors are quieter. Personally, I like that I can easily hear my teammates, particularly on open circuit. I have, therefore, never found that a quieter motor draws me to one unit over another.

One last thing to do with the motor is the way that speed is controlled: i.e., constantly variable speed or preset gears. This is important to me because it lets me truly speed-match with my teammates and not have to approximate and stop/start all the time (which I was having to do with a previous unit of mine).

Here, too, some folks don’t care. But on a dive like one I did a few years back where we scootered almost a mile at about 60 m/200 ft (and another one just last year in Canada in poor vis for about the same distance), keeping the team together was very important and was easily accomplished with a variable speed control. That meant we could concentrate on reaching the intended target (and in the case of the Canadian dive) get back to where we had started from.

Trim and Buoyancy

Let’s move on to trim and buoyancy. Call me lazy, but I want a DPV that offers perfectly neutral and in trim right out of the box (assuming I have correctly chosen the fresh or saltwater weighting. I have been known to forget to remove the saltwater weight…) My current and past units do that with a small weight that can be removed for fresh water, but one of my recent units (that was also not inexpensive) absolutely did not. In fact, it took many dives of fussing around to get it sort of close. That really irritated me. If you know the weight of your unit and what you need to put in it, the calculations to achieve that are relatively simple; so, I can’t understand why DPV manufacturers don’t do it. This has been the case with several other DPVs that my students have brought to class that required a lot of messing around to make them behave in the water.

If you like DIY projects, that’s great. But me? I just want to go diving. And, at the price point my units are at, I just expect them to be somewhat trimmed and neutral out of the box.

What about overall weight? The reason I temporarily went away from my units of choice was, in fact, weight. In the end though, the other aspects mentioned above were far more important to me than the weight differences between various units and, though I completely get that weight is a consideration for some, for me it’s sometimes an unfortunate consequence of choosing the unit that I have. It, too, lies lower down on my priority list. I dive mainly from boats and in caves, though, so I completely get it if you love to dive from shore all the time and so want a lighter unit. The units I choose to dive are for sure more of a lump to carry when shore diving.

How you charge your DPV is an option with certain manufacturers offering a charge without opening the body. Personally, having had both I don’t see the point of this as I am always going to want to look at all my O-rings, check my connections, and inspect the motor compartment for signs of issues prior to a dive, making opening the body a necessity.

This brings me to my next point. If I’m going to invest in a DPV I also want to buy one from a company that I feel has longevity. A few of the brands out there have wonderful units but are a little more homemade; this makes me nervous about being able to reach out to the manufacturer in, say, 5 years. Of course, any company can go under and disappear: that’s just business. This was a small but present consideration for me: choosing a unit that was made by a company that is established, has a factory, and makes a decent number of units that are available globally.

This brings us to worldwide parts availability. I do a fair bit of travelling, sometimes with my units or I rent the same unit where I go. It’s important to me that, if I go somewhere and the DPV breaks down—because, as stated, these are electromechanical machines that work in water, so at some point may well fail—that I can source some spares. Not all DPV manufacturers have such a global reach.

Don’t Forget the Accessories

Now that you’ve got yourself a DPV, were you hoping the potential financial bloodbath is over? Oh no no no. Now we need to investigate accessories— although I’d suggest doing this before picking a unit to make sure it has a good complement of added bits and pieces.

There are plenty of things to choose from here. Amongst the most useful are mounted compasses and bottom timers, many of which are integrated into one. Other manufacturers offer mounting hardware for diver computers and other tools.

That said, some of the proprietary units by the likes of Suex and Seacraft offer lots of added perks. The Suex Eron-D, for example, connects to the battery, giving you real time burn information. If coupled with their Synapsi nose cone, it will even give you speed and can navigate you to a particular spot or back home after some exploration.

Seacraft offers similar options with a slightly different implementation.

DPV-mounted lights exist that power from the DPV’s main battery or simply attach to the body with various mounting hardware.

Various stands are available for storage and transportation of the units, although the more DIY-savvy of you will no doubt be able to knock something up with some plywood or acrylic.

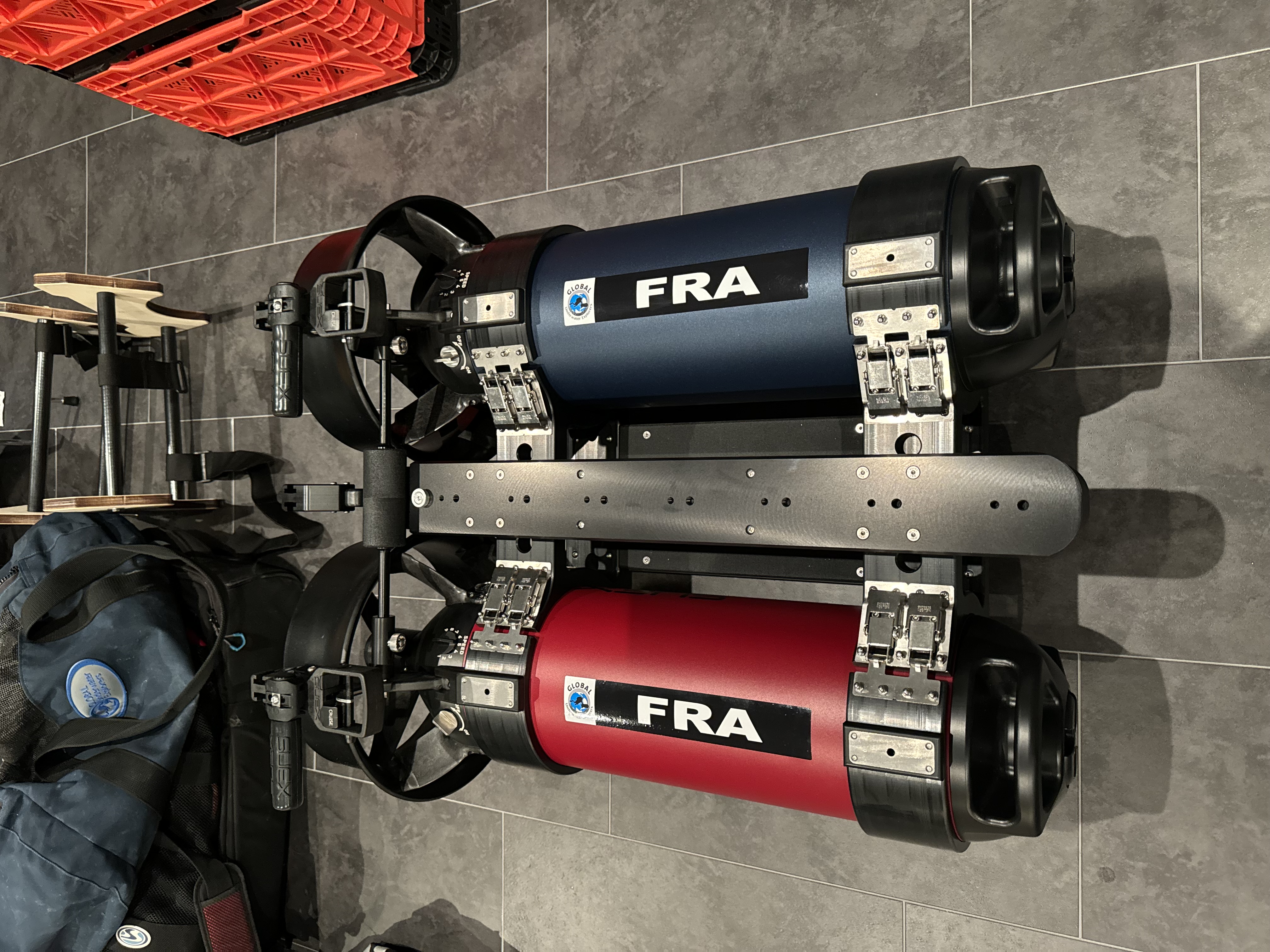

Camera mounting options come in all shapes and sizes and, to that end, Suex and Seacraft also give you the ability of mounting two DPVs side by side to create a stable platform for the larger camera setups as well as a plethora of toys dedicated to the armed services exclusively.

Carry bags and cases exist but you can also always contact a flightcase manufacturer who can custom build you whatever you need.

Travelling With Your DPV

This brings me neatly to my last point: travel. Many of my students proclaim with glee, “I am going to travel with my DPV!” Much as that may seem like a great idea, the reality of travel with DPVs is somewhat different.

Unless you are on a well-funded project with good logistical support, travelling with a DPV can be a challenge. Most of the top units run with powerful lithium ion batteries which the airlines will not let you fly with. Some manufacturers offer Nimh (Nickel Metal Hydride) alternatives for travel, and some have come up with ways of disassembling the batteries into smaller acceptable lithium units, but then you have all the added failure points of all the extra connections you have just created. There is then the size and weight of the units themselves pushing your airfare into excess luggage territory (and we all know how the airlines like to scalp us when it comes to added bags and special items).

If I am able, I drive to my dive locations and take my DPV. If I must fly, and I need a DPV for my dives, I simply rent one from a reputable source at the other end.

Yes, there are smaller, lighter DPVs. Yes, some even work with power tool batteries. But none of these fit into what I would consider as a DPV I would use in some of the diving I enjoy. So, for me, these are not an option.

If I get really stumped and cannot secure a unit, then I change my plans to not rely on a DPV.

Remember what I said at the top of this paper: they are a tool, and it’s important not to give up on kicking whenever possible. Given that we all love to dive, in the end, whether I have a DPV or not does not detract from my enjoyment of diving. I try not to get too hung up on always having my DPV. I use one when I need it and leave it if I don’t

One last point is the fun aspect of always diving with a DPV. Sure, when I got my first unit, I loved aquabatics: Barrel rolls, loop-the-loops, and the like. But after a while, that got old and the unit just became a tool. This does not mean I don’t still enjoy a roll or two, but I don’t go diving with my DPV just to do that.

While these are just a few considerations to note in your search for a DPV, I hope I’ve provided a good number of elements to ponder. Notice that I have not pointed to any one unit being better than another. Even if, on paper, one is faster and another is lighter, the right unit for me may not be the right unit for you. With all that in mind, I hope you will do some research before you go with the specs on paper.

Also, these are my opinions. They have been formulated over many dives with many different units. The community is full of different units, so find a buddy who will do a DPV swap with you—even for just a few minutes—and try a few out. Some you will love, some will leave you feeling indifferent, and some you will hate. This is all a part of choosing the right unit for you. Enjoy this process, as it can be a lot of fun and adds to the social aspect of diving.

Happy DPV shopping!

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Shop ‘Til You Drop: Comparing Tech DPVS by Nadia Lee and Martin Pieters

InDEPTH: He’s Got The Power: Meet Tech’s 22-year old Go-To DPV Guy by Mark Cowan

InDEPTH: Diving Rocks! The Traverse from Ship Rock to Bird Rock by Francesco Cameli

Andy Davis Blog: An Ultimate Dive Guide to Diver Propulsion Vehicles

Francesco is Italian but was born in Nice, France and grew up between London and his hometown of Genova. He speaks four languages and currently resides in Los Angeles, California. Francesco spent his childhood summers freediving in Portofino where he developed a love of the sea. The work of Jaques Cousteau and Luc Besson’s film The Big Blue were responsible for his desire to become a marine biologist. As things would turn out, however, he followed a career in music where he has become a successful recording engineer and owner of two world-class recording studios. Once he tried scuba, Francesco was hooked from his first dive. He is now an avid tech and cave diver and instructor, as well as a budding underwater photographer. He currently teaches the GUE Recreational and Fundamentals curricula as well as Technical Diver 1.