Cave

Cenotes on the Edge—Preserving Mexico’s Underwater Heritage

We offer a sobering update on the state of the Yucatán Pennisula, post-Tren Maya, conducted by Stratis Kas with three Yucatán-based diving instructors/ explorers and a local environmentalist.

THE TALKS: Round Table Rhetoric with Stratis Kas. Lead image: Cenote Nariz (Otoch Ha), photo by Valentina Cucchiara

Featuring; Alondra Fernández, Emőke Wagner, Ricardo Castillo, and Pepe “Tiburón” Urbina.

Forget the postcard clichés. A cenote isn’t a pretty swimming hole—it’s the beating heart of the Yucatán aquifer, and every tourist dollar can either keep that heart pumping or stop it cold. Policy, not passion, will decide whether these caverns become museums of what we destroyed or classrooms for what we saved. Real progress isn’t measured in miles of track but in the depth of water we leave drinkable. This isn’t just another tourism problem; it’s an ecological alarm bell. If you’re ready to confront what we’re really risking—and whether it’s already too late—then buckle up.

Welcome to the conversation we can’t afford to avoid!

KAS: Hey Pepe, Alondra, Emőke, and Ricardo—thanks so much for sitting down with me. I know that speaking out about environmental issues in Mexico isn’t always easy, so I really appreciate your willingness to do it anyway. Personally, I’ve been hooked on the cenotes since my first cave dive; I go back every year because it’s some of the most beautiful—and exciting—diving I’ve ever done, and I care deeply about keeping them healthy. If those cenotes could talk about the Maya Train and the new golf courses, resorts, and condos rising above them, what do you think they’d say about the choices we’re making on land?

Pepe: If the cenotes could speak, they would be screaming “Help!” It’s not just the train—the train is simply an extension of all the damage we’ve caused over the years with golf courses, recreational parks, hotels, and condos. We build on top of them, fill them in, and destroy their hidden treasures and the water they hold. Instead of taking steps to restore what we’ve broken and protect what remains, we’re multiplying our efforts to wipe it all out.

Alondra: I think the cenotes would tell us they’re suffering terrible pollution. Every day, more homes and businesses spring up, bringing more people who want opportunities here. That growth has seriously damaged the ecosystems. If the cenotes could speak, they’d beg us: “No more pollution, no more people—please help us build a truly sustainable industry.” In many cenotes, owners focus only on getting visitors to spend money. They bulldoze entrances to create open-water areas for snorkeling, swimming, and freediving—whether you’re a cave diver or not doesn’t matter as long as you pay. That drives prices up, and even local residents can’t afford to share these amazing places. It breaks my heart to see the cenotes so sad today.

Emőke: I agree. I’ve been here less than ten years—in geological terms, that’s nothing—and I’ve already watched tremendous damage to caves, cenotes, and jungle. Lately, it feels like entire areas vanish overnight. The core issues are education and regulation. Local builders and communities don’t know—or aren’t taught—how to protect caves. There are virtually no local rules, so anyone can do whatever they want. They might shut down a construction site temporarily, but it inevitably resumes. The money-driven push for new developments threatens the very places we love. If this continues, in ten years there may be almost nowhere left to dive, and that’s devastating.

Ricardo: We have to see the bigger picture: It’s not only the cenotes, but also the jungle and everything around them that’s under pressure from sheer visitor numbers. In 2000, Quintana Roo saw far fewer tourists; by 2019, it was 16.7 million visitors, and last year it hit 21 million. Saving cenotes isn’t just about loving caves—it means rethinking a tourism model that consumes vast resources. Water use is a prime example: People stay in jungle domes and take two or three showers a day. They also leave behind batteries and trash deep in the wilderness. But the root problem is money. Every landowner wants their own “Dos Ojos” operation, complete with hundreds of divers and snorkelers each day. When you’re up against that kind of revenue, preservation loses every time. Sadly, I fear these cenotes will collapse or vanish within a few years unless we change.

That’s a real wake-up call, guys. You said the cenotes would be “screaming for help” because, rather than fixing past damage, we’re multiplying it and fast-tracking their disappearance. So let’s talk about our own backyard. As divers, it’s easy to point the finger at mass tourism, but what concrete steps can we—both professionals and weekend cave junkies—take to shrink our footprint and give these places a fighting chance?

Emőke: Of course we’re guilty too. We’re part of the industry, and we’re the ones bringing clients in. Everyone wants a piece of that cake. From my experience, whenever I talk with landowners or scout new cenotes, the goal isn’t preservation. They’ll say, “This cenote is too small—we’ll open it up more for you next week.” I have to explain, “No, leave it as it is.” I show them not just its beauty, but that it’s a freshwater reserve they depend on. Yet most still think the water supply is endless, crystal clear, and permanent. It’s hard to change that mindset when there’s almost no educational material, and many don’t even realize what they have.

Still, I believe there’s a way to visit responsibly and help preserve these sites. Every diver, snorkeler, or tourist can do simple things: Don’t leave trash or tape strips behind, avoid banging your tank on walls, and leave as little trace as possible. I pick up those little blue-tape ID strips on the dive-site floor, even though I’m guilty of using them myself. Ricardo’s right about visitor numbers. Nowadays, traffic and crowds are insane, and Playa del Carmen has become a diving and recreation hub. If each of us adopts low-impact habits and shares what we know, we can still protect these amazing places, even amid the industry’s massive growth.

Stepping back, what’s the single biggest misconception people hold about Mexico’s underwater world, and how does that myth shape the way we treat it?

Alondra: Most visitors arrive at Río Secreto with nothing but “sun and beach” on their minds. At the cave entrance I ask, “Do you know what we’re doing today?” and they usually say, “We’re touring a cenote and maybe snorkeling to see what’s underneath.” I explain that we’re actually entering an underground river—the very place where the Mexican Caribbean begins—and give a short, friendly overview of why caves matter and what lives in them. When a catfish glides past, someone always gasps, “Something survives here?”

As soon as they realize the water is fresh and that the region has no surface rivers, the next questions come naturally: “Is this the same water people use above ground?” Yes. “So the waste from our hotels can flow straight into these caves?” Sadly, in some areas, it can. That realization helps them see their own impact and understand how the Caribbean’s water system really works so they can pass that knowledge along. Many guests expect an open-air cenote but find themselves deep inside a cave. These misunderstandings about cenotes, caves, and even the Mexican Caribbean come down to simple lack of awareness, just as Emőke noted. Once visitors grasp where they actually are and how these places fit into life in the Riviera Maya, their perspective changes completely.

Ricardo: The biggest problem with cenotes is that people don’t grasp how vast they are. Think of Mount Everest: Most people couldn’t point it out on a map, yet everyone knows it’s the highest peak on Earth. We need the same instant recognition here. When someone hears Ox Bel Ha (524 km/326 mi as of 2025), they should immediately think, “That’s the world’s largest underwater cave system.” In fact, we’re close to having the biggest cave on the planet—wet or dry.

But because no one holds that concept in mind, there’s no outcry. If the news reported that someone wanted to dynamite Everest’s summit to build a resort, the world would erupt in outrage. Here, people stay silent simply because they don’t understand the size and importance of what we have.

Pepe: People think a cenote is just a natural swimming pool—somewhere to splash, take a photo, and move on. That gap isn’t limited to tourists. Investors know the word “cenote” and can describe one, yet they still miss its full significance. Our job is to translate. Most of them aren’t out to destroy anything; they just want to make money. We have to show them that protecting the jungle, the underground rivers, the entire aquifer is the only way to keep profits flowing in the long run. Right now we talk environment, water, jungle, life, while they talk finance and return on investment. The conversations collide. We need to learn their language so they see how to make money by preserving, not destroying. Otherwise, we’ll lose everything before they realize its true value.

What strikes me most is how few people, even divers, grasp the size of these caves. That blind spot makes building on top of them feel harmless. When I first visited, I could gear up and enjoy a cave alone with my team; now we often wait in line behind a “tour.” From where you sit, how has cave diving changed over the last twenty years, and what have we lost along the way?

Emőke: Over the past two decades—at least from what I’ve read, heard, and observed—the number of people visiting the caves has risen sharply. Cave diving has become mainstream. Training is easier to find and more step-by-step, so divers with very little experience are entering caves. Cave diving now feels as common as riding a bicycle: Almost anyone can do it. The problem, as we discussed earlier, is that many people—locals, officials, and even the divers themselves—still don’t grasp that the caves need protection. In the process, we’ve lost pristine areas: untouched passages, quieter sites, fewer crowds. Even in the past ten years, access rules have shifted; landowners seem less interested in cave divers. The focus is on swimming and snorkeling—moving ever larger groups through a cenote as quickly and cheaply as possible. It’s become a massive industry.

That makes it hard to keep the sites natural. Development appears overnight: zip lines, restaurants, pools right beside the cenote. From one day to the next, everything changes.

Ricardo: In 2009, I photographed the “monster” formation in the Chac-Mool system. Three years later, in 2012, I tried to take the same shot and found the water completely milky. The clarity was gone, ruined by pollution flowing in from Puerto Aventuras. I stopped diving there after that. When I returned three years ago, the place felt almost radioactive: The whole system was filthy. Over the past twenty years we’ve watched the caves deteriorate and haven’t been able to stop it.

Landowners just want more visitors and more income. They don’t care about water quality or the jungle. If widening an entrance, cutting trees, or adding tables brings money, they’ll do it. Many come from poor families and feel ignored by the government, so when an opportunity appears, they seize it without concern for the consequences.

And as you said, Pepe, if the battle is about money, we lose. Preservation isn’t the priority; profit is.

“Preservation isn’t the priority; profit is.”—Ricardo

For each of you, what’s one positive change you see today, and one loss that really worries you?

Alondra: I became a diver because I love caves—first dry caves, now underwater ones. I’m fascinated by how they formed and what they reveal about the past. Cave diving, though, is a long journey: It demands practice, discipline, and knowledge.

I keep meeting guides who hold nothing more than a divemaster card yet earn money leading tours. Many dive shops promise, “We’ll teach you the skills to guide.” As soon as someone gets a basic cave diver certification, they start taking tourists underground. But without real training, they can’t explain how a cave forms, what limestone is, or even where the passages run. Profit is their only focus. So what have we lost? Dedication, depth of knowledge, disciplined practice. Too many people now work in this industry without understanding that cave diving is an extreme activity—especially here, where its popularity has exploded.

Pepe: It has become too easy to enter the caves. The importance has been diluted: Get in, dive, film yourself, post online. The meaning I once saw is fading, and it hurts. Years ago, we raised a huge alarm if someone drilled a single hole; now, entire areas are being destroyed for trains, condos, or by cenote owners building swimming pools and covering entrances with rocks. Much of the diving community stays silent, afraid of taxes, afraid of being denied access, afraid of trouble. In the past four years, we have lost more than we have discovered.

“In the past four years, we have lost more than we have discovered.”—Pepe

Mexico has some of the best cave divers in the world, and together we could show everyone why these systems matter. Yet it does not happen, and that keeps me awake at night. Maybe we cannot win, but we should still act—not out of hope but out of determination Even small victories are better than nothing, and if we truly work together, we might increase those wins.

Ricardo: One of the biggest problems is social media. People come to me saying, “Take me to that exact spot so I can get the same photo.” We are partly to blame because we post videos and pictures, that go viral, and divers from around the world want their own version. Today, if you don’t post it, it never happened.

Years ago, many of us tried to spread the scientific and archaeological importance of the caves. But after so long without real change, it’s hard to keep going. Small wins feel meaningless against the scale of what we face. Tourism in Quintana Roo brings in tens of billions of dollars; twenty-three million visitors came in 2023, while only about 1.8 million people live here. How do we fight that money?

Take the Maya Train. The original route followed Highway 307, an area already impacted. When construction created traffic delays, hotel owners and tourism associations pushed the government to move the line deeper into the jungle. That single episode shows how powerful the industry is.

Meanwhile, cave stability is already failing. A recent collapse in Ponderosa dropped a huge ceiling boulder—no injuries, but it’s a warning. One day we may wake up to an even bigger collapse, and I fear we cannot stop it. I speak sadly, because I do not see how we can truly save these systems.

Are we at risk of loving these caves to death? What does over-tourism really look like beneath the surface?

Emőke: It looks bad. Some of us are not taking seriously what we should do; instead, it’s turned into a local competition—who’s the better diver, who’s the better rescuer. That mindset feels toxic, and some people push it so far they almost fight over these caves. I don’t like that part of it and try to stay away as much as I can. But with tourism, we’ll simply overuse these caves until they aren’t enjoyable anymore. We can all name ten sites that have become complete nightmares. When I see that, it fills me with profound sadness. Once that damage is done, we can’t turn back the clock. All we can do now is try to stop the next cave from meeting the same fate.

“Some of us are not taking seriously what we should do; instead, it’s turned into a local competition—who’s the better diver, who’s the better rescuer. “—Emőke

Ricardo: That’s a tough question because it involves the whole industry. We’re not going to stop bringing people into the caves. We do our best to teach visitors about the cave’s importance, explain the fragile ecosystems they enter, and promote conservation, but we cannot halt the sheer number of people coming. And that influx, by itself, has a direct impact.

There’s a room in Nohoch Nah Chich where stalactites lie on the floor. It’s not just people accidentally kicking them; bubbles from our regulators break those delicate formations, too. If we truly wanted to stop this damage, we’d have to stop bringing people into the cave. Every visit leaves its mark. We can slow things down or try to educate visitors—ask them not to use certain gear—but consider the divers themselves.

Even I use a drysuit, yet without a p-valve you can’t stay submerged for more than two hours. Now picture 100 or 200 divers in a day, each relieving themselves in the water. Multiply that by 800 or 1,000 divers—those inputs will alter the cave’s water chemistry. I don’t know how we can fix or stop this.

Pepe: My life would be easier if I didn’t love them so much, but I wouldn’t trade it. I’m a better person for what I’ve learned, even if I suffer more. I know I’m part of the impact, but there’s a difference between impact and damage. Impact can be managed or given room to recover; damage is permanent.

“There’s a difference between impact and damage. Impact can be managed or given room to recover; damage is permanent.”—Pepe

When I arrived here, you practically had to be an advanced diver to visit a cenote. It wasn’t a law—Mexico has no real regulations—but it was an unwritten rule. That ensured divers had good buoyancy and minimized harm, and it let dive shops legitimately offer advanced training.

Now anyone can go: “I don’t care if you haven’t dived in ten years, I’m taking you in.” We have to fix that. Talk to landowners, engage with community leaders, and pressure dive-shop owners. This can’t continue. We’re already running out of cenotes to visit. I love Chac-Mool, but I haven’t been there in five or six years. Taj Mahal was one of my favorites, but they’ve freaking destroyed it. Calavera, Gran Cenote… so many places we just avoid now. The cloud over Angelita is disgusting. The Pit, once sacred, is now compromised. Zapote used to be off-limits, and now it’s worse than Xcaret.

There is room to change. We won’t eliminate tourism, but maybe we can eliminate the worst kind. I hope so—or at least I’m going to fight for it anyway.

“There is room to change. We won’t eliminate tourism, but maybe we can eliminate the worst kind.”—Pepe

Time for the big issue now. If the Maya Train is inevitable, what’s the single biggest threat it poses to cenotes—and can that risk be mitigated?

Emőke: My biggest fear is what will happen once the train starts running every day. Constant vibrations could weaken the limestone, and I picture waking up to headlines about a section collapsing beneath a passing train. As a diver, the thought of swimming under those tracks and seeing cracked pillars terrifies me.

Once the line is active, there’s no undoing the damage. The only real “silver lining” would be if the train never ran. Then the jungle could grow back, though the underwater harm would already be done.

If the project is finished, maybe we could at least use the service road beneath the tracks to ease traffic, since the main highway is already sinking from its own faulty construction. Without that kind of rethink, we’ll just add new problems to the old ones.

In the end, the train’s vibrations will fracture the limestone and invite disaster. It’s heartbreaking—and genuinely scary.

Pepe: Unfortunately, we were not able to stop the train in the Mayan jungle, and we’ve lost at least 120 cenotes that were open along the route. No one knows how many underground springs were hit. Every borehole, support pillar, and day-of vibration weakens the limestone, and the jungle canopy that once protected it is gone. The damage is permanent and will only spread if we let it.

Yet from the coast up to 20-30 km/12-19 mi inland, a vast cave network still survives. We have to keep that system from “catching the infection.” The train is now a magnet for new roads, condos, pools, hotels, and golf courses. Landowners see profit, not the Maya ruins, hidden cenotes, or jaguars, pumas, and peccaries that still live here.

Some of us are working to have this area declared a protected reserve. Right now, it’s just words on paper; if it becomes law, it will still be up to the community to enforce it. We’ll lose some fights, but we have to keep pushing. What’s gone is gone, but there’s still a lot left to save.

Ricardo: The train is a done deal, so our focus has to shift to what springs up around it. Anything built next to those tracks will put even more stress on the caves. We can’t roll back what’s been done, but we can push to limit further harm: no new roads under the rails and no fresh wave of hotels or housing right beside them. The key, now, is to slow the impact of every new project before it makes the situation worse.

Alondra: The biggest danger inside the caves is structural. We already see ceilings breaking; one small collapse can send visibility to zero and turn an ordinary dive into a rescue scenario. That risk will only rise once the train starts vibrating overhead. Diesel pollution is another worry in some systems. Fuel is already seeping in, and even if we pump it out, the ecosystem takes a permanent hit. Our job is to reduce these threats as much as possible and accept that some damage can’t be undone.

It sounds as if the tracks may do only half the damage, and the development they attract could finish the job. Given that reality, can tourism and conservation honestly work together here, or are we just telling ourselves they can?

Ricardo: Honestly, no. Most cave divers put conservation first. We see the damage and try to stop it. Mass tourism treats nature like an all-you-can-eat buffet: Use it up, then move on. In Tulum, even well-informed business owners look away. They’ll admit the problem, but say, “It’s my livelihood,” and carry on. Tourism and conservation pull in opposite directions, and we divers are stuck in the middle—expected to bring customers while somehow protecting the caves. Making those two goals line up is incredibly hard.

Alondra: It’s a two-sided coin. In theory, tourism and conservation can co-exist. At university, we studied policies that balance visitors with protection. But, here, we lack the money, staff, and enforcement to turn those textbook ideas into reality.

Ok. If saving our underwater treasures means strict limits—like permits or diver caps—are we prepared for that, or are we hooked on growth?

Ricardo: Changing the industry won’t be easy. Big dive shops have payrolls and bills; they won’t just stop bringing people in. Better training and higher standards can soften the impact, but they won’t erase it. I don’t see a simple fix.

Pepe: I’d take tough limits any day. We should have set them from the start. Losing some income is better than losing irreplaceable fossils, artifacts, and clean water. Even within the cave diving world, we argue over what “protection” means, but we have to decide together. Anything beats the last twenty years of unchecked expansion.

Alondra: I’m with Pepe. We have to begin somewhere, and that “somewhere” is now. Limits don’t kill good diving; they just shape it. Many individual pros are ready, but the wider industry isn’t, and we’ll clash over which rules to adopt because everyone has different goals.

“We have to begin somewhere, and that “somewhere” is now. Limits don’t kill good diving; they just shape it.”—Alondra

I’m with you—better to lose a few dollars than another fossil—but setting real limits takes political muscle, not just good intentions. Right now, what scares you more: a careless diver scraping a formation or an official rubber-stamping the next big construction?

Emőke: Reckless politics are the main threat. Real change has to come from the top, and our voices alone aren’t enough. One political decision can wipe out an entire cave system.

Alondra: Both divers and politicians do damage. I’ve watched untrained divers pocket Mayan bones; at Azul Ha I went looking for a skull on the bottom and found it gone. Someone had taken it, and the owner had no idea. Landowners can be just as harmful. A few months ago in Yucatán, my team found a cave with a tiny entrance; we cleared rocks, mapped the passages, and shared everything with the owners. Two months later we came back to find the hole blasted wider, stairs installed, and a steel platform so more visitors could pour in. So three groups endanger caves: uneducated divers, short-sighted landowners, and politicians.

Ricardo: Politics is the biggest danger. Quintana Roo has almost no clear environmental rules for caves, yet we advertise these very resources to tourists while destroying them. Existing laws track how the money is spent, not how nature is protected. No government will act when conservation doesn’t pay. We call that “progress,” but really it’s the jungle being erased.

Pepe: I agree. Most officials here don’t understand caves, aquifers, or limestone systems, even though every big hotel project requires geotechnical studies. They know the voids exist, but there’s more money in a new resort than in saving a patch of jungle. Politicians care only about power and profit; they won’t suddenly become environmentalists. We need other tactics: protest, scientific evidence, working with landowners, and above all, a way to translate conservation into financial terms. If they see 20,000 potential votes tied to cenote protection, they’ll notice. We have to show everyone how beautiful and how vital these systems are so that preserving them looks like a smart investment. Divers and environmental advocates need to act more responsibly and speak more loudly.

Ricardo: Reining in careless divers would help, but their impact is tiny next to policy. Guides and instructors can enforce better behavior, yet the real damage comes from decisions driven by the tourism industry. Quintana Roo earns about 20 million USD a year from visitors; diving is only a sliver of that. Caves matter to everyone because they hold the region’s freshwater, but divers alone don’t carry economic weight. Governments listen to resort owners, not to people who represent “three pennies” of the big pie. Still, we have to keep raising our voices. No one else will protect these systems, so it’s up to us, even if the odds look impossible.

After everything you’ve said about politics, profit, and protection, I’m split. The caves put Mexico on the world diving map, yet they’re also our most fragile sites. So tell me—does the future of Mexican diving really lie underground, or should we be steering new explorers toward other waters as well?

Ricardo: Divers move here every year to train, dive, and start businesses, so yes, cave diving is a huge part of Mexico’s diving future.

But Mexico isn’t only caves. We have world-class sites at Cabo Pulmo, Revillagigedo, Banco Chinchorro, Arrecife Alacranes, and all along the Gulf: The reefs and wrecks off Veracruz are amazing. There’s the Sea of Cortez, and Isla Guadalupe is the best place anywhere to see great whites. People come because they can sample many kinds of diving, not just reefs like in Indonesia.

Tourism, industry, and the economy will keep growing around these resources; what may change is where that growth centers. In ten years, we could all be based in Mérida, because those caves are still healthier. As one area is overused, the industry slides to the next. With proper regulation, we can preserve these systems and keep a thriving, eco-friendly dive scene.

Alondra: I agree the future of cave diving is here. We have the best classroom, from recreational to technical levels, but we need to spread visitors across the country. Forming alliances with other regions would balance the load.

Cave diving has huge pull on social media; those photos inspire people, and we can use that influence for good. Technology helps, too. When Ricardo and I began exploring (not even diving yet), we wore helmet flames that barely lit the walls. Now, our lights blaze like the sun, and we worry about bubbles scarring formations. Maybe one day rebreathers will be standard. As gear improves, so do our horizons, and our responsibility.

Who knows what lies deeper? Risk has kept us out of some passages, but tech will get us there, and I hope it also helps us protect what we find. I’m itching to dive farther, to hunt unknown wrecks between Cozumel and Playa, to explore hidden reefs and blue holes like the new one we found in Chetumal. There’s still so much to discover, but exploration must always pair with protection. We learned from Cousteau’s dynamite in Belize; now we have better tech and a stronger conscience. We can go farther while safeguarding what we love.

Would you ever take a government official cave diving—and if so, what do you hope they’d learn?

Ricardo: I already have. One of my students was a member of Mexican Congress. After she learned cave diving, she pushed through a federal reform that granted personalidad jurídica (legal personhood) to cenotes and cave systems in Mexico. Since 2021, they’re formally recognized in law, not just “empty space underground.” Sadly, the wording exists on paper, but little has changed in the field.

Pepe: Same here. I’ve guided national and international officials—once even a head of state (he didn’t tip!). I’ll take anyone underwater if it helps them feel the awe I do; political influence used well is priceless. Communication is our main defense.

Emőke: I haven’t taken a Mexican official yet, but I’d welcome the chance. I’d give the same thorough briefing I give every student and show, step by step, why these caves are key to the region’s water and heritage. Any policymaker reading or listening is invited. Come see it with your own eyes.

Pepe: For years, we’ve begged officials to witness the damage from the Maya Train. Opposition politicians have visited—some only for a photo op, others truly engaged—but the decision-makers pushing the project stayed away. Only in the past month have new staff from SEMARNAT and CONANP joined us. We guided them on foot and by snorkeling; they saw the beauty and the destruction, and they left unharmed. No revenge taken! We hope that experience shapes the protections they draft next.

Alondra: Exactly. They need to feel how fragile this place is. At Cenotes Urbanos, we say, “The Riviera Maya begins in the caves.” If officials grasp that, they’ll understand why safeguarding the whole ecosystem matters. I’m on board with everything you’ve all said.

Thank you guys for speaking so plainly and for carrying the cenotes on your shoulders long after the cameras switch off.

So, fellow diver or simple traveller, before you cannon-ball in, ask yourself: Where does your water come from, where does your waste go, and would you accept limits on your fun to keep a site alive?

Dive operators: Train fewer tourists better, not more tourists faster. A dead cave won’t pay the bills.

And, to all of us—humans uniquely capable of wiping out an ecosystem we haven’t even finished mapping—we still get to choose. I’ve watched seedlings reclaim bulldozed jungle in a single rainy season; nature wants to recover if we’ll only quit tripping her at the finish line.

See you—every one of you—where light meets limestone.

Pepe “Tiburon” Urbina summarizes the situation. WTF! Filmed by Joram Mennes.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: SAVE THE CENOTES! (2022)

InDEPTH: Tren Maya is on the Wrong Track! An Update by Alessandra Figari, Elias Siebenborn, Roberto Rojo, and Guillermo D. Christy. (2023)

Help Preserve the Cenotes: Cenotes Urbanos

Alondra Fernández

Alondra Fernández was born in Teziutlán, in Sierra Norte de Puebla. A tourism management professional by training, she took up speleology at age 16 in Hueytamalco, Puebla, and has since joined exploration projects with several caving groups. She served for four years as secretary of the Puebla State Speleology Association (AESPEP) and now teaches vertical technique courses for the International Centre of Adventure and Nature and for Cenotes Urbanos.

Links

Instagram: @alofernasi

Instagram: @thewhitelineprojectmx

Instagram: @cenotesurbanos

Emőke Wagner

Emőke Wagner is a Hungarian cave diving instructor and explorer from Sopron who holds a 2013 human-kinesiology degree from Semmelweis University. After several years in healthcare, she turned professional diver, teaching in the Maldives (2014-17) before moving to Mexico to pursue caves full-time. A GUE instructor since 2016, she teaches Cave, DPV, Tech, and Recreational courses in English, German, Spanish, and Hungarian. She has logged 4,200 dives—over 1,200 in caves, 500 decompression, 300 wreck, 700 DPV—and has mapped more than 55 km/34 mi of new passage with a record penetration of 6.37 km/3.96 mi. Her exploration spans Mexico, Florida, France, and Hungary with roles in MCEP (2018-20), BEL (2020-23), Cocom (2024-25), and, as project leader, PURE (2025). Major exploration zones include Chuup Ich, Akalche, Yax Chen, La Concha, Abejas, and Cocom. Blending academic rigor with field skill, she promotes safe technique and conservation while mentoring the next generation of cave divers.

Links

Web: www.emokegue.com

Instagram: @emokegueinstructor

Ricardo Castillo

Ricardo is a Mexican diver, instructor trainer, and expedition leader with 20-plus years and 7,000 dives behind him. From basic SCUBA to trimix CCR cave courses, he teaches the full spectrum while guiding expeditions into oceans, caves, and flooded mines worldwide. His camera has followed him to Antarctica, the Arctic, South Africa, Mozambique, the Mediterranean, Canary Islands, Maldives, Iceland, Norway, Hungary, Poland, Finland, the Great Lakes, Cocos, Galápagos, Bahamas, Truk Lagoon, Scapa Flow, Hawaii, Cuba, Tonga, Fiji, Thailand, Indonesia, and countless Mexican reefs and cave systems. Television crews often tap his expertise for documentaries on shipwrecks, sharks, and subterranean exploration. Holding instructor credentials with NSS-CDS, SDI-TDI, and DAN, he specializes in decompression procedures, mixed gases, rebreathers, and underwater imaging; his deepest dive is 137 m/450 ft, his coldest –1.7 °C/29 °F. Ricardo co-owns Dive Rite Mexico and Zotz Local Diving Experts in Playa del Carmen.

Links

https://www.facebook.com/ricardo.castillom.5

https://www.instagram.com/richardiving

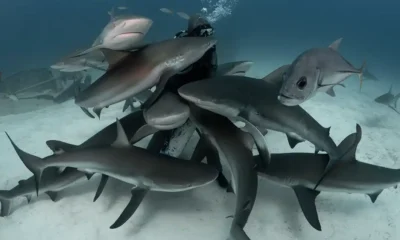

Pepe Urbina

Pepe Urbina, also known as Pepe Tiburon, is a dedicated environmentalist deeply involved in protecting the natural treasures in the jungle and sea. His pioneering efforts in the early research and conservation of Bull Sharks were instrumental in transforming Playa del Carmen into a world-leading destination for diving with this species, an activity now regulated by CONANP.

Pepe’s impact extends beyond marine life; he played a role in developing the Mexican Caribbean Biosphere Reserve and is a vocal advocate for environmental education, sharing his knowledge at various national and international forums. He has actively worked to stop illegal and ecocidal real estate, hotel, and mining projects. Most notably, as a founding member of the Sélvame del Tren collective, he served as the primary complainant in the legal injunction that halted the construction of the Mayan Train’s Section 5 South. Through his multifaceted efforts, Pepe Urbina stands as a crucial defender of the human heritage and natural resources of Quintana Roo.

Links

FB: https://www.facebook.com/pepe.tiburon.2025

IG: @pepe_tiburon

Speaking Sidemount: https://www.sidemountpros.com/speakingsidemountpodcast/2024/1/1/episode-92-pepe-tiburon-tren-maya-a-disaster-in-the-making

Stratis Kas, a Greek-Italian professional diving instructor, photographer, film director, and author, has spent over a decade as an esteemed Advanced Cave instructor, leading expeditions to extreme locations worldwide. His impressive diving achievements have solidified his expertise in the field. In 2020, Kas published the influential book Close Calls, followed by his highly acclaimed second book, CAVE DIVING: Everything You Always Wanted to Know, released in 2023. Accessible on stratiskas.com, this comprehensive guide has become a go-to resource for cave diving enthusiasts. Kas’s directorial ventures include the documentary “Amphitrite” (2017), shortlisted for the Short to the Point Film Festival, and “Infinite Liquid” (2019), which explores Greece’s uncharted cave diving destinations and was selected for presentation at TEKDive USA. Kas’s expertise has led to invitations as a speaker at prestigious conferences including Eurotek UK, TEKDive Europe and USA, Tec Expo, and Euditek. For more information about his work and publications, visit stratiskas.com.