Conservation

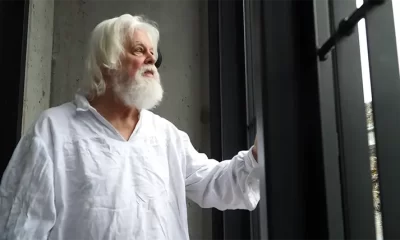

Can We Save Our Planet? What About Ourselves? Interview With Sea Shepherd founder Paul Watson.

InDEPTH editor and designer Amanda White poses the BIG questions to environmental activist Captain Paul Watson, founder of Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and the architect behind its strategy of aggressive non-violence. His answers may enlighten you, surely will surprise and may even move you to tears. What motivates the 70-year Environmental Hero of the 20th Century to keep up the fight despite widespread ignorance, apathy and greed? Find out.

By Amanda White

Images courtesy of Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

We all know what climate change is. We all know that we are running out of time. But yet, very few people are actually taking any significant steps to slow down the destruction of our home. This includes protecting all of the species on it. We are currently in the middle of the Holocene extinction sometimes referred to as the Anthropocene extinction or sixth mass extinction event, yet we are not panicking and governments, businesses and the human race do very little to save themselves. So why is that? Maybe it is because people often feel powerless or like their behavior will have little effect on the outcome.

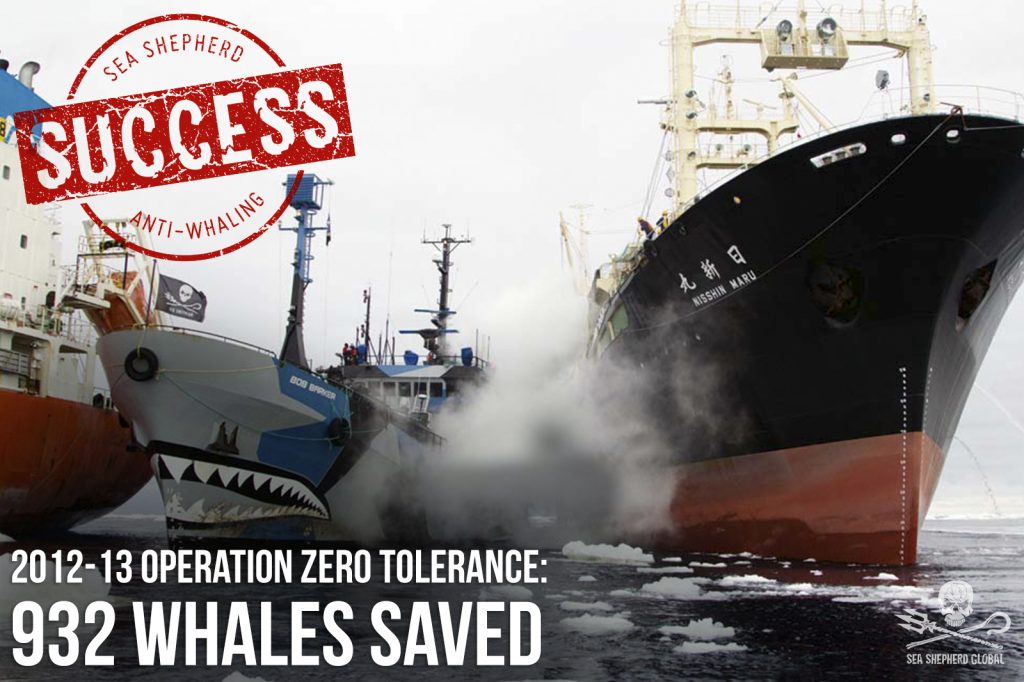

One man has been an inspiration to many through his direct action to save marine life all over the world—Captain Paul Watson. Watson, who at ten years old realized that his life’s purpose was to protect animals, has been doing just that for 60 years. As an adult, for years he worked on freighters and deep sea vessels , and it was because of this as well as his participation in a demonstration at the U.S. and Canadian border that he and several others created Greenpeace. Watson and the group were demonstrating against nuclear testing on Amchitka Island in the Aleutians. He continued his activism, and in 1977 he founded Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, whose mission is to be “a global movement to defend, protect and conserve life and diversity in the ocean”. Today it truly is a global movement with chapters in over 40 countries. It is one of the few organizations that is actively protecting wildlife. Their current campaigns are, “Saving the Vaquita”, “Preventing IUU Fishing”, “Protecting Wild Salmon”, “Beaked Whale Research”, “Protecting Sea Turtles” and “Ocean Cleanup”.

We recently sat down with Watson, who Time Magazine named as one of the “Top 20 Environmental Heroes of the 20th Century,” to see what his thoughts are on where we are today with the environmental movement, COVID-19, and to ask him how he stays positive through his 60 years of committed effort to save us all (including the viruses).

InDepth: Many scientists, conservationists, and some notable world leaders have been warning us about the destruction of our planet for some years. Why do you think we, meaning people as a whole, as well as governments, have been slow to make changes to protect our future?

Paul Watson: Well, I would agree that the scientists have been doing this, but I certainly wouldn’t agree that world leaders have been saying anything. I mean they’re not doing a damn thing, really. Except holding conferences where they just talk a lot of babble and really don’t act on anything. That’s been going on since 1972, when the first environmental conference took place. I can’t think of any world leaders that have done anything or intend to do anything. But there is a growing movement of people around the world who understand that if things are going to change it has to come through our passion, our imagination and our courage. And we are seeing more and more people getting involved in that. But at some point, it’s going to be all rather academic because the laws of nature are going to kick in and nobody will have any choice, really, but to respond. The warning signs have been there for decades and have been ignored.

Why do you think people are ignoring the message?

Well, because, basically, people just don’t give a damn about anything, really. When it gets right down to it. If you look at every social revolution in the history of humanity, it has always been led and carried out by about no more than 7% of the population. The other 93%, they just go along for the ride and do whatever they’re told. It’s always been that way. And this is no different. Politicians always take credit for these things after the fact. Governments cause problems, they don’t solve problems.

You’ve been leading this movement since 1969. How do you think it’s changed so far in terms of protecting the ocean?

On the positive side, how it’s changed is more and more people are involved. More and more people are aware. In 1972, we took out a billboard in the city of Vancouver that had a big word in yellow, ECOLOGY. And on the bottom of the billboard it said, “Look it up, get involved.” Nobody even knew what the word meant.

So when it comes to awareness and involvement, yes, there are more people involved, more people are aware. However, things have changed on a different front. What we could do in the 60s, 70s, and even the 80s, we can’t do anymore. The world has become more repressive. The campaigns that we did, we wouldn’t even have gotten anywhere off the ground.

The people who lived in the 50s, 60s, 70s and even into the 80s, lived in the most opportune generation in the history of humanity. Certainly the wealthiest and certainly the freest time ever. We’ll never see that again. It’s been taken away from us. And as ecological conditions deteriorate, governments will respond with more authoritarianism. It’s going to happen. Just look at the media. Trump goes on about fake news. It’s not fake news. It’s no news. The media decides what they are going to cover. And environmental issues are on the bottom of the list.

Over 1000 environmentalists have been murdered in the last decade. You wouldn’t know that from reading it in the media. But there was a major, major problem just last week off the coast of Russia in Siberia. A massive die off of sea life. You’ve got to get your issue of New Scientist to find out that happened. So the media controls all the communications and what we know. The media defines reality. And over the years, we’ve had to learn how to work within that media culture.

How do you get the media’s attention then? Do you have a system for working with them?

We dramatize these issues because there are four elements of media that can’t be ignored: sex, scandal, violence, and celebrity. And every story has one of those elements. And if you don’t have it, you don’t have a story. And so we try to incorporate that into our campaigns. We dramatize things.

To give you a good example, probably one of the best examples, I had to stop a wolf kill in northern British Columbia in the Yukon Territories. We had all four elements. Killing wolves is violent: they’re threatening to kill us if we interfere. Violence” we have a British Columbia environment minister who took a bribe, and we caught him taking the bribe. So we had violence and scandal. So I recruited Bo Derek as our spokesperson for that campaign. And at the press conference the place was packed, and the Vancouver Sun reporter said to me, “Come on, what’s Bo Derek doing here? She doesn’t know anything. This is stupid. What does she know about wolves?” I said, “Well, you know, if I had the two foremost wolf biologists in the world here today, this would be an empty room. Nobody would be covering the story. But you’re going to write the story, it’s going to be the headline of your newspaper tomorrow, and you know what? There’s not a damn thing you can do about it, is there?” Because we controlled the elements. And that’s the way the media works.

I learned a long time ago that the most powerful weapon on this planet is the camera. If it isn’t on camera, it didn’t happen, and no one’s going to believe it. And even if it’s on camera, a lot of people don’t believe it. But still, it is a powerful weapon. One of the reasons we put together the Whale Wars show was in order to get everybody’s attention, we had to dramatize it. A lot of the things that we did in Whale Wars, the fights with the water cannons and the stink bombs and everything, that wasn’t part of the actual tactic to stop whaling. There was only one tactic that worked, and that was to block the ability to load dead whales onto the factory ship. That’s what we concentrated on. All those other things, that was for television. That was to get people’s attention. That was the theatrics that we had to utilize to get the message across.

Has your strategy for protecting marine life changed over the years?

No, back in 1977 after I left Greenpeace and set up Sea Shepherd, the strategy that I developed, I call aggressive nonviolence. We are very proud of the fact that we have never caused a single injury to anybody in our history and never sustained any injuries. But we have shut down hundreds of illegal operations through aggressive nonviolence. So we get accused of a lot of things. When anybody calls me an ecoterrorist I say, no, I never really worked for Monsanto, so that doesn’t really fit. They can call us whatever they want, but the fact is, is we don’t hurt people.

“We are very proud of the fact that we have never caused a single injury to anybody in our history and never sustained any injuries. But we have shut down hundreds of illegal operations through aggressive nonviolence.”

In 2011, I was invited by the FBI, of all people, to come and give a lecture at Quantico on environmental activism. And one of the FBI special agents said, Sea Shepherd walks a pretty fine line when it comes to the law. And I said, yeah, well, who cares how fine that line is, as long as you don’t cross the line? He couldn’t really disagree with me.

And now, Sea Shepherd has evolved from what we were before, to starting… Well, we actually started in 1999 with Ecuador, but since 2015 with numerous other countries, we are now in actual official partnerships with Liberia, Gabon, Nubia, Tanzania, São Tomé, Cape Verde, Peru, Mexico. And we are working with them to stop poaching in their waters. We provide the volunteers and the resources, and they provide the authority. And it’s been very effective. We’ve arrested 52 poachers from West African waters in the last year. And we have prevented the extinction of the vaquita porpoise in the Sea of Cortez working with Mexico.

How do you manage to stay on the right side of the law when not working with a country?

Outside of territorial waters, we still intervene under the principles of the United Nations World Charter for Nature which allows for nongovernment organizations to uphold international conservation areas, specifically in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

It’s very difficult to come after us legally. We’ve been sued many times, we’ve been taken to court many times. We have won every time. So we have not been convicted of any felonies in our entire 42-year history, and we intend to keep that record. But we do walk that line. And sometimes we have to break laws, but then we are prepared to defend the breaking of those laws in the courts. And we have won in every single case.

How did you feel about being called an eco terrorist when you first started out?

Oh, it doesn’t bother me at all. Anytime anybody disagrees with anybody, they use the word terrorist. The word terrorism is so overrated that it doesn’t even have any meaning anymore. The environmental conservation movement, even the animal rights movement, has been an incredibly nonviolent movement over all this time. It’s actually astounding just how nonviolent it is. But, you know, it’s pretty easy to demonize people just by calling them names.

Critics have called you a pirate as well!

In the 90s when they started calling us pirates. I said, okay, if you want us to be pirates, we’ll be pirates. We’ll get our own pirate flag and everything. Because at least pirates got things done. And also, when you look at the history of piracy, some of the greatest heroes in the world have been pirates. John Paul Jones, Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh. All pirates and all heroes. Pirates get things done. And also, pirates weren’t that bad. When you take a look at Blackbeard. What was Blackbeard doing? He was attacking British ships and American ships, slave ships, and freeing the slaves. And giving them an opportunity. Go ashore or you can join my crew. If you join my crew, you can rise to the level of your competence. You know, pirate ships in the 17th century had multiracial crews, multi-gender crews and everybody was equal.

Why do you think that Sea Shepherd is one of the few organizations that takes this aggressive, nonviolence tactic?

The strength of an ecosystem is in diversity. So therefore the strength of any movement has to be in diversity also. So whether that approach be litigation, legislation, education, or direct intervention, it all points to the same thing. We are all effective in our own way. So I’m not negating what other people do; I’m just saying this is what we do. But at the same time, the one thing I am opposed to is, which is really, protesting. I don’t believe in that.

You don’t believe in protests?

Protesting to me is very, very submissive. It’s like please, please, don’t kill the whales, don’t cut down the trees. And they do it anyway. And all you do is take pictures and hang banners. That doesn’t get anywhere. And also, the other bad thing about it is, with civil disobedience, people go out on the streets, they get arrested, and now they’ve got a criminal record. That pretty much renders them useless in so many ways. And really, that kind of nonviolent civil disobedience actually has been incorporated into the systems overall. So they know how to deal with it. They expect it, and they punish it. So I’ve tried to keep our people out of that.

What are your thoughts about the recent protests in the States for Equal Justice and Black Lives Matter? Do you think they have been effective?

I don’t believe in protesting for myself. The strength of any movement is in diversity. That diversity includes protesting. I happen to feel it is a submissive approach. That is my opinion. However I don’t criticize those who do. People must do what they feel is the best thing for them to do. That approach can be litigation, legislation, education, direct action, intervention, art, or protesting.

What do you think has been your greatest success?

Creating a movement, a global movement, which is what Sea Shepherd is now. I don’t run things. We are in 42 different countries and entities, and they run it themselves. We all work and cooperate to support the ships and everything. I’m not even the leader of it anymore. And why that came about is that in 2012 when the Japanese came after us in American courts, and came after me personally, we learned a lesson. You can stop an individual and you can even shut down an organization, but you cannot stop a movement. That I think has been the biggest success, creating that kind of movement.

“You can stop an individual and you can even shut down an organization, but you cannot stop a movement.”

What does it take to start a Sea Shepherd chapter in one’s own country?

You just have to organize it I guess with Sea Shepherd global. To give you an idea how Sea Shepherd chapters came about, in 1981 I got a phone call from a man in Scotland and he says, “They are killing gray seals up here in the Orkney Islands. What are you going to do about it?” And I said, “Well, I’m on the other side of the planet. What are you going to do about it?” So, we helped him set up Sea Shepherd Scotland. And he got a bunch of volunteers together, and they went up to the Orkney Islands. Very enthusiastic bunch. They walked up to the fishermen who were shooting seals, literally pulled the rifles out of their hands, and threw the rifles into the ocean. They all got arrested; that was fine. We actually ended up winning the case, and in the end, we raised so much publicity in Scotland that we raised enough money to buy the island they were killing the seals on. And now we own that island, and it’s a seal sanctuary.

That’s a great story. Do you have any disappointments about how things have evolved over the years?

I don’t really have any disappointments. I guess you have to look at my philosophy in this way. The most valuable lesson that I ever learned was in 1973 when I volunteered to be a medic for the American Indian movement during the occupation of Wounded Knee in South Dakota. We were surrounded by 3000 federal agents who were shooting at us. They killed two people, they wounded 46. We were completely outnumbered, the odds were against us; we could not win this.

I went to Russell Means who was the leader of the American Indian movement during that occupation. I said, “Look, we can’t win, the odds are against us. What are we doing here?” And what he told me really stayed with me for the rest of my life. He said, “We’re not concerned about the odds against us. And we’re not concerned about winning or losing. We’re here because this is the right thing to do, the right time to do it, and the right place to do it. Don’t worry about the future. Concentrate on the present. What you do in the present will define the future.”

All you can do about the future is worry about it. But what you can do in the present is act. And that determines what the future will be. And not to get pessimistic or be deterred.

“And what he told me really stayed with me for the rest of my life. He said, “We’re not concerned about the odds against us. And we’re not concerned about winning or losing. We’re here because this is the right thing to do, the right time to do it, and the right place to do it. Don’t worry about the future. Concentrate on the present. What you do in the present will define the future. “

Is that what you advise young people?

I tell young people all the time, don’t let people deter your passion. Just ignore them. [Swedish environmental activist] Greta Thunberg is great at doing that. But the thing is that you just can’t be stifled by the opinions of other people.

A real problem, especially with young people, is that so many times both parents and teachers… I mean I had this myself: “You can’t do that, that’s a stupid idea. That’s just not practical.” You’ve just got to ignore all that stuff. I still vividly remember when I was a child doing something. I cut up a map of the world and I put all the countries and continents together and I said to the teacher, you know, I think this was once one continent. I think they all broke apart. And they said, oh, that’s a stupid idea.

How did I know? It wasn’t that I was smarter than the teacher. Just, as a child, it made intuitive sense. So children can see things, they see knowledge that parents and teachers have long forgotten. Because they are being taught to be rational and reasonable and everything like that. And by that, they miss the gift of intuition, which is an intuitive understanding about the nature of the world.

Was there a defining moment when you knew you were doing the right thing?

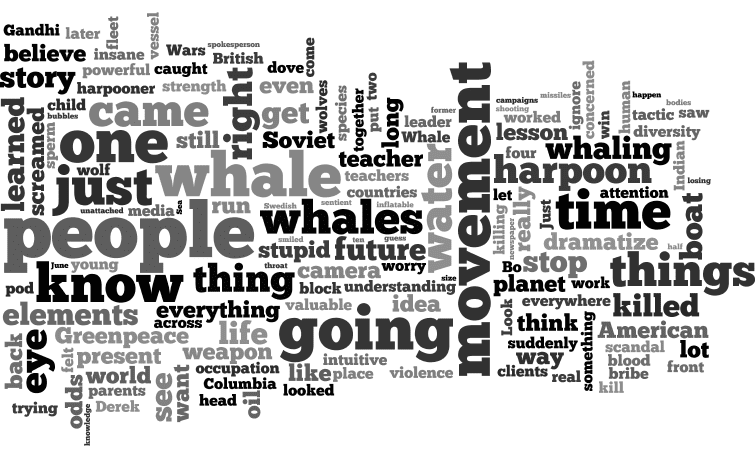

Yes. That was another lesson that I learned in 1975. My teacher in this case was a whale. In 1975, we had come up with this idea, I was still with Greenpeace at the time, to protect whales by putting our bodies between the harpoons and the whales. We were reading a lot of Gandhi. And there I was with June and Bob Hunter in a small, inflatable boat in front of a Soviet whaling vessel that was bearing down on us at full speed, and in front of us were eight magnificent sperm whales that were fleeing for their life. Every time they tried to harpoon one I would maneuver the boat to block the harpoon. And this worked for about 20 minutes until the captain of the boat came running down the catwalk and screamed into the ear of the harpooner and then looked down at us, smiled and brought his finger across his throat. And that’s when we realized Gandhi wasn’t going to work for us that day.

A few moments later there was this incredible explosion and the harpoon flew over our heads, slammed into the backside of a female in the pod of sperm whales. She screamed. It’s like hearing a woman screaming. And rolled on her side and there was blood everywhere and the largest whale in that pod suddenly slapped the water with his tail and dove.

He swam directly underneath of us and threw himself at the bow of the Soviet harpoon vessel. And they were waiting for him with an unattached harpoon. The harpooner pulled the trigger, hit him point-blank in the head. He screamed and fell back in the water rolling in agony, blood everywhere and I caught his eye. And suddenly he dove again.

This time I saw a trail of bloody bubbles coming at me real fast. And the whale came up and out of the water at an angle so that the next move was to come down and crash right down on top of us. And as I looked into that eye that came out of the water, an eye the size of my fist, so close I could see my own reflection in that eye, I saw something that changed my life forever. It was understanding. He understood what we were trying to do. I could see him make the effort to pull back. His head began to slide back into the water, his eye disappeared beneath the surface and he died. He could’ve killed us and chose not to. So I am indebted to that whale for my life.

“And as I looked into that eye that came out of the water, an eye the size of my fist, so close I could see my own reflection in that eye, I saw something that changed my life forever. It was understanding. He understood what we were trying to do. I could see him make the effort to pull back.”

As I sat there in that boat in the middle of the Soviet whaling fleet, the sun was going down and what else did I feel? I felt that the whale felt pity for us. Not because we had killed him but because we were doing what we were doing. Why were the Russians killing those whales? They didn’t eat the whale meat. They killed them for oil. Sperm whale oil is a high heat resistant oil and one of the things that makes it so valuable was in the construction of intercontinental ballistic missiles.

I said to myself, “Here we are killing this incredibly beautiful, intelligent, self-aware, sentient being just for the purpose of making a weapon for the mass extermination of human beings.” And that’s when it struck me just like that. We’re insane. As a species, we are totally insane. And I said to myself right there, I’m not going to do this for people. I’m going to do this for the others. For all these other species that we are trying to destroy. That’s who I represent. They are our clients. Not people. And in the long run it’ll benefit people.

About ten years later, in 1986, we sank half of Iceland’s whaling fleet in their harbor. A former colleague from Greenpeace called me up and said, I just want to let you know that what you did there was criminal and reprehensible, and you’re an embarrassment to the whole movement. And I said, “Look, John, I don’t care. We didn’t do this for you. We didn’t do this for Greenpeace, we didn’t do this for any human being on this planet. You find me one whale anywhere on this planet that disagreed with what we did and I promise you, we won’t do it again. But until then, we are going to continue to do what we are doing. We are representing the interests of our clients, and they don’t want to die and they don’t want to be exterminated.”

“I said to myself, “Here we are killing this incredibly beautiful, intelligent, self-aware, sentient being just for the purpose of making a weapon for the mass extermination of human beings.” And that’s when it struck me just like that. We’re insane. As a species, we are totally insane.”

So what keeps you motivated and hopeful when you’re doing these things day after day and you feel like you are fighting against people who don’t care? How do you stay motivated?

I’m not inclined to be pessimistic. I believe that the answer to an impossible problem is simply to find the impossible solution. And that can be done. In 1972, the very idea that Nelson Mandela would be president of South Africa was unthinkable and therefore impossible. And yet that became a possibility. Seemingly impossible things can have solutions if you apply yourself. Because of Diane Fosse we still have mountain gorillas in Rwanda. Because of David Wingate, a biologist from Bermuda, we still have the Bermuda storm petrel, a bird most people have never heard of but would’ve been extinct if it wasn’t for what he did. So that’s what gives me a lot of hope.

“But we can’t destroy this planet. No matter what we do, we cannot destroy this planet. It will survive. The question is, will we?”

The other thing is that, in the long run, if you take a look at the history of mass extinctions on this planet, and there’ve been five prior to this Anthropocene extinction that we are in right now. In the history of mass extinctions, they all had one thing in common. The Permian extinction wiped out 97% of everything in the ocean. And yet, 18 to 20 million years later it recovered. And every single one of them it took 18 to 20 million years to recover. So in 18 to 20 million years from now, it’s going to be a nice planet again. This whole movement is really about saving ourselves from ourselves. And also taking a lot of abuse in the process. But we can’t destroy this planet. No matter what we do, we cannot destroy this planet. It will survive. The question is, will we?

What are your thoughts on the current situation around the world with COVID-19 and zoonotic viruses?

For 20 years I’ve been predicting this pandemic. And the signs have always been there. If you read the book that was published by Laurie Garrett in 1996 called The Coming Plague, she showed us that this was happening. You know we had Hantavirus, West Nile virus and MIRS and SARS and all these other things. There’s going to be more and more of this. This COVID-19 is a harbinger of more things to come. Because when you destroy ecosystems and diminish species, we forget that the viruses run this planet. Viruses and pathogens run the planet. There are viruses associated with every single plant and animal on this planet and they… We need them. Life wouldn’t be possible without viruses.

“This COVID-19 is a harbinger of more things to come. Because when you destroy ecosystems and diminish species, we forget that the viruses run this planet. Viruses and pathogens run the planet. There are viruses associated with every single plant and animal on this planet and they… We need them. Life wouldn’t be possible without viruses. “

But when you diminish a species or an ecosystem, you set up a situation where those particular viruses associated with those particular species have to go somewhere. Where are they going to go? So those that are closest to us, like bats or primates, they are going to look at the most attractive hosts around. And eight billion of us are very attractive hosts. And they are going to jump. Now the problem with viruses, they don’t want to kill you. I’m talking like they have a conscience, but they don’t. They need coexistence. But that involves killing a lot of hosts in order to achieve that coexistence. And that’s been the history of pathogens throughout human history.

And it’s continuing because of our behavior, as you’re talking about. But not even just our behavior with the current virus, but our behavior to everything outside of ourselves.

The real disease is anthropocentrism. This idea that we are the rulers of the universe. That we are greater than all other species. Unless we learn to live in harmony with all other species, we are not going to survive. Those are the laws of ecology, the law of diversity that the strength of an ecosystem is dependent upon the diversity within it. The law of interdependence that all species are interdependent. And all finite resources. That there is a limit to growth and a limit to carrying capacity. And we are stealing the carrying capacity from other species. And that therefore then diminishes diversity and diminishes interdependence.

“The law of interdependence that all species are interdependent. And all finite resources. That there is a limit to growth and a limit to carrying capacity. And we are stealing the carrying capacity from other species.”

It’s interesting that probably 99% of us don’t realize we are doing that.

The other thing is, that humans lack two traits. One, is that we lack an ability to envision the future. And two, that we are unable to adapt to diminishment. Thirty thousand years ago that stood us in good stead, to be able to adapt to diminishing circumstances. But now, it’s very destructive. If this was 1965, and I were to say to you, “You know, in 40 years you are going to be buying water in plastic bottles and paying more for that water than the equivalent amount of gasoline,” you would’ve looked at me like, “Who the hell would do that?”

And yet, here we are. Unquestionably adapting to diminishment. We remove one species of fish, we go on to another species of fish. We forget that species of fish was there. Remember orange roughy? It was a big deal in the 1990s. You don’t see it anymore because that fish takes 45 years to become sexually mature and lives to be about 200 years old. It couldn’t keep up with the demand we made on it. Unlike salmon, which at four years become sexually mature. We can’t treat all fish species the same.

What would you propose we do?

I proposed this at the top 21 conference in Paris, but of course nobody’s going to listen to it, but I said, “If you want to save the ocean, you’ve got to give the ocean the opportunity to repair the damage that we have done to it. That means we have to have a complete moratorium on industrial fishing operations for the next 50 years, at least. It’s got to have time to repair itself.”

You know, Raytheon, the company that manufactures fish finders? You know what their motto is? The fish can run, but they can’t hide. They are bragging about the fact that we can exterminate them. That leads us to what I call the economics and the politics of extinction. That there is money to be made, profit to be made by wiping out entire species and destroying ecosystems. Because our entire economic system is based on short-term investment for short-term gain.

“That leads us to what I call the economics and the politics of extinction. That there is money to be made, profit to be made by wiping out entire species and destroying ecosystems. Because our entire economic system is based on short-term investment for short-term gain. “

Why don’t businesses adjust to be more sustainable long term?

They want to make as much money as possible in the shortest time possible so they can reinvest it in something else. What’s Mitsubishi doing in the fishing industry? They started making weapons. Now they’re into fishing. But after they wipe out the fish, they will move on to something else. For instance, they have a ten-to-fifteen-year to 15 year supply of bluefin tuna in Mitsubishi warehouses in Japan. They have enough to supply their customers for the next ten to fifteen years. They could shut down the bluefin tuna fishery and allow it to regrow. They won’t do that. And the reason they won’t do that is because, if they did, and the population of bluefin tuna in the wild began to rise, the value of the fish they have in the warehouses would be diminished. And if they wipe it out, they have an invaluable commodity in the warehouse. They can ask any price. The bluefin tuna is now the most valuable fish on the planet. It is $75,000 per fish. And it will go up. Because diminishment translates into profits.

“We are being led on this road to extinction by greedy, greedy individuals. It’s willful ignorance. They are choosing to be ignorant so they don’t see the consequences because it’ll get in the way of their profits.”

The entire West Coast herring industry is being wiped out because only one man controls the West Coast of Canada’s fishing industry. The entire fishing industry is controlled by Jimmy Patterson, a former used-car dealer, who has bought out the fishing industry and pretty much has all the politicians in his pocket, so he can do whatever he wants. Now why is he killing off the herring? Because to provide feed or fishmeal to the fish farms which are becoming a big business, which are also very destructive. We are being led on this road to extinction by greedy, greedy individuals. It’s willful ignorance. They are choosing to be ignorant so they don’t see the consequences because it’ll get in the way of their profits.

There have been some recent scientific studies that suggest that marine sanctuaries and reserves work—that the populations in those areas have started to come back.

Here’s the problem with marine sanctuaries and marine reserves. That’s where the poachers go. Most of our efforts are now protecting those marine reserves. Like in Africa or the Galapagos. But despite the fact that the marine reserve of the Galapagos where we’ve been working with the park rangers since 1999, about 600,000 sharks are taken out of the Marine reserve every year. They arrest people. You arrest one poacher and four more move in.

The motivation to continue this exploitation of resources in the ocean is just absolutely beyond control. Without any studies, the Norwegians and the Japanese are going down to exploit Krill plankton, or plankton Krill down in the southern ocean. But why are they doing it? Because it can provide a cheap protein base for factory farms. We kill 65 billion animals on factory farms every year. That’s not counting even more numbers of fish we take out of the ocean. That’s the leading cause of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, more so than the automobile industry, and the leading cause of groundwater pollution, and dead zones in the ocean.

What will it take for humans to change their behavior? Do you think it’s possible? Are we savable?

Well, I think the laws of ecology will force us. That will take care of the problem. Either it will take care of us, or we will learn. We have to abandon anthropocentrism and adopt what indigenous cultures still understand, biocentrism. This understanding that we are part of everything. We are not the most important species on this planet.

If you take a look at the earth for what it really is, a spaceship on this incredible voyage around the Milky Way galaxy, at incredible speeds, every spaceship has a life-support system. And that life-support system provides us with food, the air we breathe and regulates climate and temperature. That life-support system is a machine that isn’t run by us. We are just visitors who are having a wonderful time entertaining ourselves. But what we are doing is killing off crewmembers. And there’s only so many crew members you can kill before everything begins to break down. This planet is really run by trees and bees and worms and viruses and microbes. Those are the engineers of planet Earth. And we are killing them. And if we do, we will follow. The passengers will go down with the ship when the crew are no longer there able to operate that ship.

Great analogy. We are definitely responsible for our own destruction. How can we view ourselves as part of nature?

We need to have a better understanding of what this planet is. It’s not really the planet Earth, it’s the planet water. We are the ocean. And because the ocean is water, in continuous circulation, sometimes it’s in the sea, sometimes it’s in ice, sometimes it’s underground, and sometimes it’s in the clouds, and sometimes it’s in the cells of every plant and animal on this planet. The water in your body right now was once in ice, once underground, once in the sea, was once pissed by a dinosaur. It is the most continuous movement, a circulation of water. That is what this planet is. Without water we are nothing. Without water, you don’t even have a body. And so the protection of the ocean means protecting all parts of the ocean. Not just that of the sea. And everything that you put into the air ends up in the sea. And everything that you put in the sea ends up in the ground. It’s just constantly circulating.

“The water in your body right now was once in ice, once underground, once in the sea, was once pissed by a dinosaur. It is the most continuous movement, a circulation of water. That is what this planet is.”

You said that you disapprove of tourism, but you still encourage traveling. Can you explain what you mean?

A traveler is an explorer. Somebody that goes out and explores the world and lives with the cultures that they are in and respects that. Here’s a good example of how tourism is destroying the Galapagos, for example. The tourists go to the Galapagos and they want a nice, comfortable place to say. When I first went to the Galapagos, you could get a room for five dollars a night. Now it’s $200 a night. They are knocking down mangrove forests to build eco-tourist hotels. They are putting thousands of people out on boats to go into the ocean and interfere with everything. And of course they want to eat well, so that means they have to catch more fish in the Galapagos to feed the tourists. Now they are bringing in cattle from the mainland because the tourists want their steaks. When you travel, like a good friend of mine, Cliff Ward, he walked the Great Rift Valley in Africa with just his pack sack. And the only thing he had was flour and he was teaching people on the way how to make pancakes, which was interesting. But he didn’t take anything. Tourists go in and they take and they cause destruction. So that’s the difference. A traveler doesn’t do that.

How can we make that transition happen? Is it even possible to make that transition on a broader scale?

I don’t know, I think this COVID-19 is putting pretty much an end to a lot of it. I don’t know. Will people improve? Again, as long as we have this anthropocentric point of view, we’re not going to do it. We have created a world of delusions. Religions. I call them a collective mass psychosis. We have convinced ourselves that this God or whatever God, is like a human. It’s like a giant monkey in the sky or something. I don’t know. But what we have become is a bunch of overly conceited, narcissistic, naked apes who’ve become divine legends in our own mind really. We’re not what we think we are.

What are we then?

We’re simply part of nature. And that’s the only way we are really going to improve. And we are not very successful. Hominid primates have been one of the least successful groups of species on this planet. We’re the last survivors. How many species of beetles are there? Seven hundred thousand. How many species of monkeys? Or fish? When it comes to hominids, we wiped out our competition. And we even have the audacity to say that we are the only thinking animals. We are not. We don’t even have the most complex brain on the planet. The human brain is 17 cm³. The orca brain is 6000 cm³. The sperm whale brain 9000 cm³. And those brains are four-part brains to our three-part brains and their convolutions in the neocortex area are far more pronounced than ours. But they can’t make tools. And that’s how we equate intelligence. You’ve got to be able to make a tool to be intelligent.

“I measure intelligence by the ability to live in harmony with your environment.”

We define what intelligence is. If a dog walks into a room, your dog can tell you who was there yesterday, you can’t do that. So from that point of view, they are more intelligent when it comes to their sense of smell. Every species is intelligent, including plants, in relation to their environment. I measure intelligence by the ability to live in harmony with your environment. I was debating a whaler in Norway on this, and he said, “But Watson, you say that intelligence is the ability to live in harmony with the natural environment. By that criteria, cockroaches are more intelligent than us.” I said, “You know, Lars, you are beginning to understand what I’m trying to say.”

What can our readers do to support Sea Shepherd and to protect the ocean?

Well, people can be involved with Sea Shepherd in many ways by volunteering to be a crew member, by being a shore volunteer. And that involves everything from supporting our ships to cleaning up the beaches. Or by supporting us with contributions. Those are the three ways that people can get involved.

But more importantly, people can be involved by looking at what their ecological footprint is, the things that they consume. All of our ships, for instance, are all vegan ships. You don’t have to be a vegan to join the crew but you have to be a vegan while you’re on the crew. It’s hypocritical if we don’t do that. But we are not going to force it, to say, you’ve got to be a vegan. But we are trying to set an example. It is amazing how many of our crewmembers, and there have been thousands of people who have been on crews, it’s amazing how many people have discovered that they didn’t die by adapting to a vegan diet.

We are all born into a society as hypocrites. We have no choice. The thing is, you can do everything to mediate that, but the fact is that we have no choice. We are born on a treadmill of consumerism and behaviors that we’ve inherited. And all we can do is try and get ourselves off of that treadmill as best we can. But if you drop out completely, you might as well go live in a cave and be a hermit and not accomplish anything. So you’ve got to do what you do with the resources that are available to you. But also with the recognition of the destruction that a lot of those resources cause.

What about Sea Shepherd’s ecological footprint? Is it something that you worry about?

One of the things we get criticized for is that we burn fuel, the boats burn a lot of fuel every year and we are called hypocrites for doing that. But we couldn’t catch the poachers if we didn’t. But we actually are contributing and not causing the problem, we are contributing to the solution. And how that is is that we shut down 52 poaching vessels in Africa this last year. That’s 52 boats that will not be burning fuel. So for every whaling ship, every fishing boat that we shut down, we are actually preventing the consumption of fuel by going after them, in a way. But we have one sailing boat. I wish that all the vessels could be sailing boats, but you can’t catch poachers with a sailing ship.

How To Support Sea Shepherd:

Check out Capt. Watson’s new organization: Captain Paul Watson Foundation

Capt. Paul Watson’s Online Store

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: The Looming Environmental Apocalypse: Deep Sea Mining by Capt. Paul Watson

Capt. Watson contributed several articles to aquaCORPS Journal back in the 1990s and attended the TEK.95 conference in San Francisco.

aquaCORPS #9: Wreckers: “Why I Sink Ships” by Paul Watson

aquaCORPS #10 Imaging: Return of the Seal Slayers by Paul Watson

Amanda White is the managing editor for InDepth. Her main passion in life is protecting the environment. Whether that means working to minimize her own footprint or working on a broader scale to protect wildlife, the oceans, and other bodies of water. She received her GUE Recreational Level 1 certificate in November 2016 and is ecstatic to begin her scuba diving journey. Amanda was a volunteer for Project Baseline for over a year as the communications lead during Baseline Explorer missions. Now she manages communication between Project Baseline and the public and works as the content and marketing manager for GUE. Amanda holds a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism, with an emphasis in Strategic Communications from the University of Nevada, Reno.