Community

The Future Of Food Is In The Sea

In the face of a warming world, the fields and forests of the sea, aka seaweed, may well be the key to feeding a hungry population while combating climate change in the bargain. Here certifiable Venezuelan dive geek, Carlos Lander, explains why we may want to put seaweed on the menu. Side of kelp with those veggie burgers?

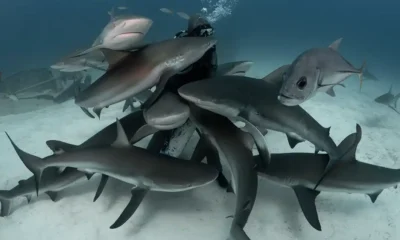

by Carlos Lander. Lead image courtesy of Jason Brown, www.bardophotographic.com

?? Predive Clicklist Seaweed by Tindersticks

There is a deserved urgency in climate change discussions, but we might discover a key piece of the puzzle in a diving domain—the ocean. Our seas contain a unique ecosystem that harbors countless secrets we are only beginning to understand. Can one of those secrets save the planet?

If you ever dived into a tangle of seaweed and watched with fascination as the undulating waves cradled and carried the sea grasses with magical ease, it probably did not occur to you that this underwater forest could hold the key to slowing climate change—and so much more. Let’s dive in and examine the possibilities.

Seaweed’s Culinary Past: A Short Selection

Seaweed is not a weed at all—it’s a loosely-defined group of both prokaryotes (e.g. sea grasses) and eukaryotes (e.g. algae, microalgae) that occupy both marine and freshwater environments. Seaweed grows in oceans, lakes, and rivers, and algaes alone represent 16,000 species.

When we think of seaweed consumption, some think of Asia’s seaweed salads and sushi rolls. But, seaweed consumption is a centuries-old tradition throughout the globe.

The Americas

The use of algae in the pre-colonial Americas has been overlooked, perhaps due to colonial destruction of Mesoamericans’ written documents.

Today we call algae spirulina; however, the Aztecs1 collected a bluish-colored mud called “tecuitlatl,” which roughly translates to “poop rock.” In bloom seasons, they filled entire canoes with it, drying the macroalgae under the sun and using the final product to make tortillas. Spanish conquistadors reported that they tasted like cheese.

Curiously, in Venezuela2, native people once used an algae-based degreasing paste and included algae in their clay pottery mixes to increase cohesion, eliminate bacteria, and provide elasticity to the clay during the curing process.

In Chile, seaweed has been widely consumed since pre-colonial eras. This tradition spread gradually from the coastal (Indigenous) people to the cuisine of the colonists, perhaps due to ease of transportation and preservation. To harvest the seaweed, they cut it by the stalkipe and waited for the current to wash it onto the beaches3. After the drying process, the products were sold at the market.

The most widely eaten seaweed by the First Nations along the northwest coast of North America was red laver. These vitamin- and mineral-rich algae were popular particularly in times of famine and food shortages. They dried or fermented the seaweed and processed it into cakes, pounded it and stored it in small flakes ready to be eaten as snacks, or cooked it in soups and stews.

Another interesting example, but this time from the northeast coast, is Native Americans’ use of seaweed in place of salt brought by colonists. They also used seaweed for storage and food preparation; for example, they layered algae on the heated stones in pit cooking, which protected the food from being overcooked and avoided contamination from sand. This provided a distinct flavor, as well.

1 Chronicles of Missioners Francisco Hernandez Y Fray Toribio de Benavente. Spirulina is a non-differentiated filamentous cyanobacteria common in alkaline lakes and it is cultivated in lakes.

2 Archaeological Chronicle of Venezuela

3 Seaweed Consumption in the Americas, Jose Luis Perez_llorens

Europe and the Middle East

Europeans in the Middle Ages burned algae to extract salt—a practice that continued in France until 1950.

In 1940, the French phytologist Pierre Dangeard4 described that, in Lake Chad (lying in portions of today’s Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria), the Kanem people produced a salty, algae-based cake. Scientists continued to discover cultures spanning the deep Sahara Desert5 to the Red Sea that also prepared similar biscuits from algae.

A Worldwide Phenomenon

Archaeological and ethnohistorical data proposed a cross-cultural adoption of seaweed as food. Icelanders brought the tradition to North America, and other migratory movements proliferated the practice.

The tradition of eating seaweed declined with colonial development, but in the mid-19th century the migratory movement to North America from Irish, Scottish, and Asian populations re-introduced seaweed to the local gastronomy, which still informs today’s restaurant industry; more about this later.

4 Linnaean Society of Bordeaux Magazine

5 Belgian expedition led by the biologist Leonard, see: Paniagua-Michael J, Dujardin E, Sironval C 2004. Aztecan’s Chronical.

The forest of the sea can save us all: The role of seaweed in climate change

Climate change discussions are commonly dominated by three topics: clean energy, reduced greenhouse emissions, and carbon dioxide extraction from the atmosphere. Economically speaking, removing huge amounts of CO2 from circulation has become a price that society must pay.

Let’s zoom out to the global economy. Many countries with lower GDPs currently rely on fossil energy—it’s still not cost-effective to implement 100% fossil-free energy at scale, especially for governments that simply don’t have the capital to invest in alternative energy infrastructure. Instead of sanctioning countries that can’t afford to go green, CO2 removal technologies could address some climate change issues without punishing late adoptees of fossil-free philosophy.

In a world where seaweed farms already exist, we have a cost-effective, scaled mechanism for growing the crop while reaping the benefits of plant-based carbon capture.

The ocean is the biggest surface on the planet, and it’s a key climate regulator—it stores and transports heat, carbon, nutrients, and water all around the world. Theoretically, we can develop a climate-altering-crop6. Macroalgae already has a place in our culture, and the pharmaceutical, agriculture, and food industries are already harnessing its unbelievable genetic diversity.

Seaweeds in general are among the top carbon-capturing organisms and actually perform much more efficiently than trees. Seaweeds’ symbiotic relationships with bacteria reduce photosynthetic waste, and algae uses its entire surface area to photosynthesize. Seaweed grows fast and is economically viable.

Given the massive ocean surface, there is a potential opportunity for offshore marine farms to enhance natural production. Seaweeds require minimal nutrients, they grow year-round, and scientists continue to develop new ways to use and synthesize algae.

Although it is possible that mass production of algae could have a positive effect on global warming—since it could potentially absorb gigatons of atmospheric CO2—it is unclear exactly how an effort like this could affect deep sea marine creatures. But, successful permaculture seaweed farms already exist among thriving fish and shellfish populations. Seaweed is an ideal permaculture crop, it reduces water’s acidity, and it supports an ideal environment for larvae and juvenile marine life. Seaweed farms, while in their infancy, promise to be a multibillion-dollar industry supplying pharmaceuticals, textiles, and (interestingly) food production.

6 Tim Flannery

Seaweed as food

There are three edible algae suitable for aquaculture—red, green, and brown algae.

Red algae

Sheets of red algae are commonly sold as nori.

Nori is cultivated in cold and shallow marine waters, where it is collected and sold for use in various products. You’ve likely encountered it as the “paper” employed to wrap sushi. You can buy it at the supermarket in sheets or in a dehydrated, wrinkled form. Red algae offers substantial nutritional value, featuring significant iodine, manganese, as well as vitamins A, B2, B9, and C.

Another common red algae product, Irish moss or carrageen moss, has a foothold in the food industry. By weight, carrageen mosses comprise nearly 10% protein and about 15% mineral matter; they are also rich in iodine and sulfur. The food industry commonly uses it as a thickener and stabilizer in milk products and other processed foods, and it can even be used in beer brewing.

Carrageen moss is found in abundance in the Atlantic Ocean.

Brown algae

Wakame, or sea mustard, is a highly nutritious species of kelp farmed on the coasts of the Indo-Pacific Ocean. It has a strong flavor with slightly sweetened touch. It is most often used in soups and salads.

Kelp (Laminaria) has many uses: It’s used in toothpastes, shampoos, salad dressings, puddings, cakes, dairy products, frozen foods, pharmaceuticals, and fertilizers.

In addition to the iodine and iron generally found in all marine algae, brown algae offer calcium, folate, magnesium, and vitamin K. Recent studies suggest that vanadium and fucoxanthin, substances present in brown algae, help to control diabetes via blood sugar regulation and increased production of omega-3 (though they are found in small quantities in the algae).

Green algae

Sea lettuce, sea palm, and sea grapes are the most common green algae, they are rich in beta carotene and collagen. While the data is new, green algae may offer anti-tumor properties in cancer prevention applications. Green algae are commonly commercially harvested in lakes and ponds.

Miscellaneous algae applications

- Researchers recently used blue-green algae to successfully power a computer’s microprocessor for longer than six months. Their findings could revolutionize the energy supply for the Internet of Things—the network of physical devices that facilitates the web.

- Although still in their infancy—and not yet cost-effective at scale—several government agencies (including the US Department of Energy) and companies are funding research and development programs to produce biofuel from algaes in the face of rising fossil fuel costs.

- Biofuels composed of 40% algae have been used on test flights in jet applications.

- Microalgae are a present consideration for wastewater treatment applications—they have the potential to decrease nitric and phosphoric qualities of treated wastewater.

Algal bloom concerns

Algal bloom can be very hazardous for the environment and local economies; these blooms are mainly composed of cyanobacteria, a blue-green algae variety that can leach the water of oxygen and produce toxic chemicals lethal to zooplankton, fish, and other water dwellers.

Climate change has produced warmer water temperatures and prolonged droughts. Blooms are more common under these conditions (especially drought ,which increases water salinity) .

Conclusion

The ocean holds immense resources and potential for future generations of innovators—culinary experts and climate scientists alike.

Perhaps a quintessential example of underwater innovation is Nemo’s Garden, an experimental agricultural operation growing terrestrial plants under the sea.

Marine and freshwater algae could be a key piece in the climate change puzzle. It has the potential to extract gigatons of CO2 from the atmosphere when farmed at scale. But, if we cultivate it in deep marine trenches, the potential effects on these ecosystems are still unclear. However, seaweed still shows promise as a permaculture crop. We may only learn more via trial and error.

In the interest of scale, a global seaweed production effort must accommodate even countries with low GDP—on both a governmental and community level. It could provide economic opportunity for investment in sustainable energy, decreasing the incidence of future fossil fuel burning. But, this effort requires global advocacy and up-front financial investment.

The pharmaceutical and biofuel industries are already harnessing inland cultivation of freshwater algae, introducing new applications every day.

The combination of seaweed’s potential environmental power and the precedent of algae consumption throughout history create an excellent opportunity for both ecological innovation and culinary education.

Ultimately, the introduction of seaweed as a climate change solution must be equal parts global effort, scientific enterprise, political project, and social endeavor.

Thanks to Maria Fernanda Capecchi and Luis Lemonie for research assistance..Maria is a biologist dedicated to algae in all aspects from farming to cuisine. Luis is an archeologist that shares my passion for scrutinizing the human past.

Thanks also to InDEPTH editor Nic Haylett, whose extraordinary editing skills helped to organize and clarify much of this important work. Finally, we’d like to offer thanks to tech entrepreneur Joe Howell for encouraging us to explore the importance of sustainable ocean food sources.

Dive Deeper

zme science: Onshore algae farms could feed much of the world while reducing the environmental impactby Fermin KoopIt’s a promising new type of farming—but there are many hurdles in the way.

BBC: The plans for giant seaweed farms in European waters

NSW GOV: New opportunities to support and harness underwater forests

PubMed Central: Microalgae, old sustainable food and fashion nutraceuticals

NYT: The Johnny Appleseed of Sugar Kelp

GZERO Media: Introducing GZERO’s Coverage on Hunger Pains: The Growing Global Food Crisis

Carlos Lander—is a father, a husband, and a diver. A student of economics, he’s a self-taught amateur archaeologist, programmer, and statistician. In his view, the amateur brings a unique mindset to the table and, paired with expertise from professionals, can discover advantages in the field. I studied economics at university. My website is Dive Immersion.