Community

Adventures in Picture Making

Photogrammetry is one of the new tools that is revolutionizing marine archaeology and enabling explorers to share their discoveries with scientists and the public alike. Seattle tekkie Kees Beemster Leverenz discusses some of the methods he and his team-mates have worked through to bring back home the image, err data. You won’t believe your eyes!

by Kees Beemster Leverenz

The SS Thistlegorm

Marcus Newbold and I found ourselves in the cargo hold of the Thistlegorm, a World War II steamship that’s famous for being packed to the brim with antique motorcycles, trucks, and weapons. Our goal was simple: take just one photo that did justice to the sheer volume of material in the ship. The Red Sea is warm, the SS Thistlegorm rests in shallow water, and we were both equipped with rebreathers, so we had practically all day to set up the shot.

The plan was to set up a makeshift photo studio 100 ft/30 m underwater in a rusty ship. After an afternoon of begging, we scraped together a half dozen video lights and a couple super-bright strobes from our friends that had come along with us. We arrived in the cargo hold quickly and began the methodical process of placing and adjusting lights for the best effect, careful to avoid stirring up any silt.

I’d occasionally hear Marcus say something through his rebreather mouthpiece as he worked his way around the hold placing his lights, lighting up the two pickup trucks that dominated the space. While it’s never entirely clear what anyone is saying when they try to talk through a mouthpiece, you can usually tell if someone’s happy or sad, excited or mad. Even without turning around, I could hear from the tone of his muffled words that he was pleased with how his half of the lighting job was shaping up.

Although Marcus seemed pleased, I was having a lot of difficulty. One light in particular was causing me grief, and it was key to getting the photo we imagined. It was the most powerful off-camera light we had, and it needed to be positioned in exactly the right orientation or it wouldn’t go off. After several minutes of adjusting, I managed to wedge it in exactly the right spot. The room was lit, and it was time for Marcus to take his place in the center of the room for the picture.

Unbeknownst to me, Marcus had adjusted his weight right before the dive, and was having trouble getting comfortable in the water. His buoyancy just wasn’t quite right. So, instead of floating motionless for the picture (like he’d done the previous few days), he started swimming laps. I took a series of photos, but none was exactly right. Every time, there was something wrong with the picture: either Marcus was too far away, or he was too close. His eyes weren’t in focus, or the lights didn’t go off.

Amidst the controlled chaos of the photoshoot, a group of divers from another boat swam into the cargo hold to explore. We’d spent nearly an hour in one of the world’s most popular wrecks, so we couldn’t expect to spend the entire day alone. However, we weren’t planning on them making any changes to our set!

To my horror, I watched from across the room as one of the divers reached down and picked up my carefully wedged strobe: the one that needed to be in exactly the right spot to work. He turned it over in his hand curiously, unaware of what he’d just done. An instant passed, and then I heard a funny sound from the other side of the room. It was the sound of pure frustration emanating from Marcus, believing that this diver had accidentally ruined our set. While his voice was muffled by his rebreather, the emotion was crystal clear.

I wasn’t the only diver to hear the noise, and our new friend’s curiosity immediately vanished. The diver quickly replaced the light, Marcus’ initial reaction subsided, and fortunately we only need to make a few quick adjustments to get the shot. The six video lights and three strobes we used for the final image allowed us to capture the depth and the breadth of the room, while keeping Marcus and the 40’s-era trucks well lit. That simply wouldn’t be possible with only the lights attached to the camera.

Off-Camera Lighting

Using off-camera lights is challenging; it’s much easier to mount your lights on your camera and be done with it. However, breaking free of the standard setup makes it possible to take artistic and documentary photos that you’d otherwise never be able to take.

There are a few major benefits to taking your lights off your camera. The most significant advantage is that off-camera lights typically reduce the distance light travels through water. With only on-camera strobes, light travels from your camera rig to the subject and then back to your camera (where it’s captured). That’s a lot of water to go through, and it significantly affects both the color and the amount of light you get. With your lights mounted closer to your subject and off your camera, the light emitted only travels about half the distance. That means richer colors and a better lit picture.

While Marcus and I shot pictures in the hold of the Thistlegorm, we took full advantage of these benefits. The room would have appeared dark and blue even with multiple bright lights mounted to my camera. While placing lights around the cargo hold was effective, this strategy has some significant disadvantages; the setup process takes a long time, and the entire time while you’re preparing you’re subject to the environment. You could stir up silt and cause bad visibility, you can lose a light between two trucks, or you can have someone come in and accidentally steal a strobe. Whatever the case, placing lights around a scene isn’t ideal for all situations, especially when you don’t have a lot of time.

Al Qamar Al Saudi

Our best opportunity to try a different method came a few days after we dove the SS Thistlegorm: Marcus, Alex Adolfi, and I had the opportunity to dive the Al Qamar Al Saudi. The Al Qamar Al Saudi is a roll on/roll off ferry with a large car deck and room for 600-700 passengers. It’s a significantly newer ship than the SS Thistlegorm, having been completed in late 1970 and sunk in 1983. The car bay is also much larger than the cargo hold of the Thistlegorm. During our briefing before the dive, the Red Sea Explorers crew (our hosts) mentioned that the car bay was particularly spectacular, running nearly the entire length of the ship… but that it was a challenge to light.

Challenge accepted.

Fortunately for us, there’s significantly fewer divers visiting the Al Qamar Al Saudi than the SS Thistlegorm. Unfortunately for us, that’s because it rests in about 270 ft/83 m of water. The ferry is a deep, technical dive. Even with our rebreathers, a relatively short time on the bottom could mean hours of decompression to avoid injury.

The wreck is enormous, and even with scooters just getting inside the car bay would take a lot of time. Once we got inside, we wouldn’t have the luxury of time to scout or stage lights. The space was much larger, so we decided to try a different technique: we’d have Alex and Marcus hold the lights and illuminate the inside of the ship as we went. While using divers to hold off-camera lights isn’t quite as reliable as staging a scene, it is much faster than the methodical process of placing lights around a space.

Both Alex and Marcus were equipped with three lights each. The first light was the same that most GUE divers carry: a good quality primary light, used only for communicating within the team. The second light was a wide-beam video light mounted underneath their rebreathers, pointed back and slightly up, placed to make the divers more visible. Without this light, their dark drysuits and black fins would have been invisible against the darkness in the background of the hold. The final light was another video light that each diver held and pointed at anything they found interesting.

Although our dive was complicated by a scooter failure, we managed to get several decent shots from inside the Al Qamar Al Saudi during the few minutes we got to spend inside, thanks to the small array of diver-mounted off-camera lights. Marcus and Alex did an excellent job of lighting up the background of the car bay while my on-camera strobes lit up the foreground. With only on-camera lights, the depth of the space would have been hidden in the shadows, and if we had decided to place lights around the space, it’s unlikely we would have gotten any photos at all! As a side benefit, lighting a scene with video lights often makes the dive itself more fun for the divers involved, since the space is lit up everywhere, not just for the camera.

Off Camera Lighting for Poor Visibility and the PB4Y Project

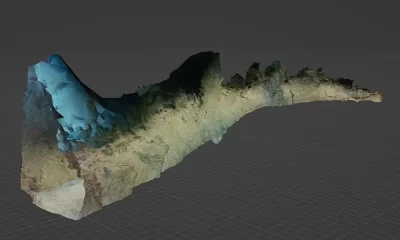

While artistic photos are a lot of fun, that’s not the only application of off-camera lighting. Support divers and bright off-camera lights have been essential for our 3D photogrammetry projects here in Seattle. 3D photogrammetry uses hundreds or thousands of images and specialized software to reconstruct a complete 3D model of a target, often a wreck. Each picture doesn’t need to be beautiful, but the subject does need to be well lit, so we can apply a lot of the same techniques we used in the Red Sea to our projects at home.

Our most recent target was the PB4Y, a four-engine bomber from World War II that crashed on a training mission into our local Lake Washington. It’s been there since 1956, disturbed only by a US Navy recovery attempt just after it sank. While the airplane is in remarkable shape and the structure is nearly completely intact, the water that surrounds it is dark, cold, and murky; far from the clear blue water of the Red Sea.

Lighting a scene is always challenging when visibility is bad. However, proper application of off-camera lighting can reduce the effect of poor visibility on your final picture. Most of the time, poor visibility is caused by silt or other small particles suspended in the water. Backscatter occurs when light bounces off particles floating in the water back towards the source of the light, causing hundreds or thousands of tiny points of light in your picture. If the source of the light is right next to the camera, as is the case with camera-mounted lights, backscatter can significantly reduce the quality of your images.

By using diver-mounted lights (similar to how we lit the Al Qamar Al Saudi), backscatter can be nearly eliminated. Instead of the light bouncing off the particulate matter in the water towards the camera, it bounces back towards the support divers. The bulk of the light that is captured by your camera ends up being much “cleaner.”

We’ve managed to model a few targets successfully so far in our dark, cold, and murky lake, and a project the size of the PB4Y has only been successful thanks to skilled lighting divers who illuminated the airplane from just the right angles. For this application, we find it’s best to have one, two, or sometimes even three divers actively moving around our target, lighting the way for the photographer.

For this project, each of our support divers carried a pair of 33,000 lumen BigBlue video lights. Since the two lights are quite heavy underwater, we connected them with a pair of float arms and rigged them with two bolt snaps. When they’re not in use, they can be easily stowed (in the same way as a stage bottle is attached).

While we’ve been fortunate enough to have access to a lot of powerful lights, even a primary light can be effective for the purpose of cutting down backscatter or making an artistic photo pop off the screen, if you choose your subjects correctly and you’re willing to make a few mistakes along the way.

Dive Deeper:

Are you interested in learning more about underwater documentation or photogrammetry? Explore GUE’s Documentation Diver or Photogrammetry Diver courses.

Kees Beemster Leverenz is an enthusiastic diver and GUE instructor from Seattle, Washington, who enjoys getting in the water as often as possible. He has been deeply involved with GUE Seattle since it was founded in 2011. Currently, Kees is contributing to both local and global photogrammetry projects, as well as assisting with cave and wreck exploration projects whenever possible.