Latest Features

A Visual History of Subsea Habitats

DEEP’s Phil Short takes us for a tour of our collective efforts to live and work beneath the sea.

by Phil Short of DEEP Research Labs. Images public domain unless specified.

The ocean is the entire planet’s life support system, and it’s critical that we understand and conserve it.

But much of the ocean is still to be explored because of the challenges in accessing it.

Subsea human habitats offer a means to gain that crucial access to the ocean, and engineering a new generation of underwater habitats is central to our mission at DEEP: to make humans aquatic.

Luckily, DEEP is building on many years of innovation in subsea habitation, which we explore here.

Since Alexander the Great first descended beneath the waves in a bell, mankind has dreamed of sustaining life under the sea. We’ve established an “off-world” presence before: via 11 space stations, from Salyut 1 to the International Space Station. And, in the ocean, we have experimented and dabbled in establishing a presence in our own world’s ‘Inner Space.’ From Robert Stenuit spending 24 hours at 61 m/200 ft in the Link Chamber in 1962 to missions at Aquarius Reef Base, there have been more than 65 subsea habitats throughout history.

Here’s a glimpse of the highlights of six decades of subsea habitats.

But first, it’s useful to understand the differences between habitat types. Not all subsea habitats are the same—far from it.

Floating habitats: In a floating habitat, the human housing is in the underwater hull section of a floating structure—really more a viewing chamber than a habitat.

Access shaft to the surface: Some habitats feature access via a shaft to the surface above water. While depth is limited, visitors can enter and exit without the need to compress or decompress since normal atmospheric pressure is maintained. The Underwater Observatory Tower in Eilat, Israel is one example.

Semi-autonomous habitats: Semi-autonomous habitats are accessible by either diving or performing a Transfer Under Pressure (TUP). These habitats receive energy and breathing gas via an umbilical cable. Most subsea habitats have been of this type (includingAquarius and Sealab I & II).

Autonomous habitats: Autonomous habitats feature self-contained reserves of breathing gas and power. Some are capable of vertical manoeuvring for deployment and recovery. A good example is Conshelf III.

A Subsea Habitat Timeline

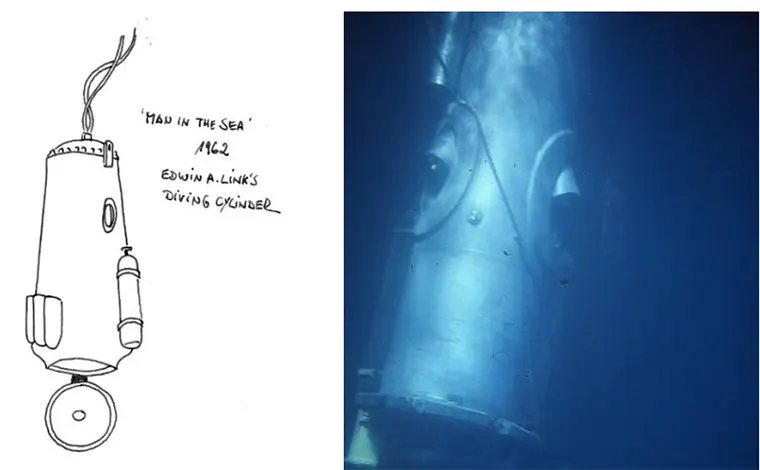

In 1962, the “Link Chamber” (named after Ed Albert Link, the inventor of the “Link Trainer” flight simulator), also known as SDC (Submersible Decompression Chamber), was deployed in 61 m/200 ft of water with a single Aquanaut, Robert Stenuit (*1) aboard. Stenuit was destined to become the first ‘Aquanaut’ upon completion of the mission.

Under the directive of Captain Jaques Eves Cousteau (*2), Continental Shelf Station (Conshelf) I (“Diogenes”) deployed in 10 m/33 ft of water from Marseille. Two Oceanauts (Albert Falco and Claude Wesley) spent seven days in the habitat and made five hours of excursion dives each day.

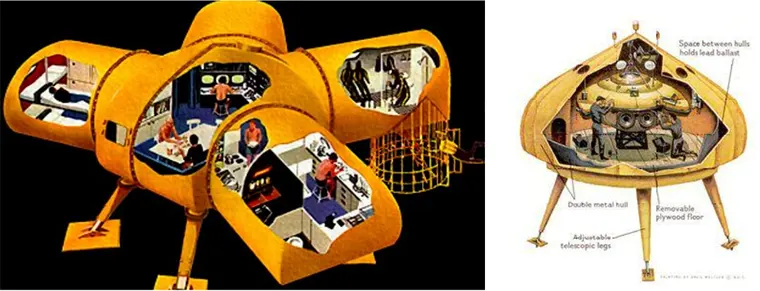

In 1963, Conshelf II (“Starfish House”) and a submarine hangar for the SP-350 “Diving Saucer” (Denise) were deployed in 11 m/36 ft. In addition, a smaller habitat, “Deep-cabin,” was deployed at 30 m/100 ft. Five Oceanauts spent 30 days in Starfish; simultaneously, two Oceanauts spent a week in Deep-cabin.

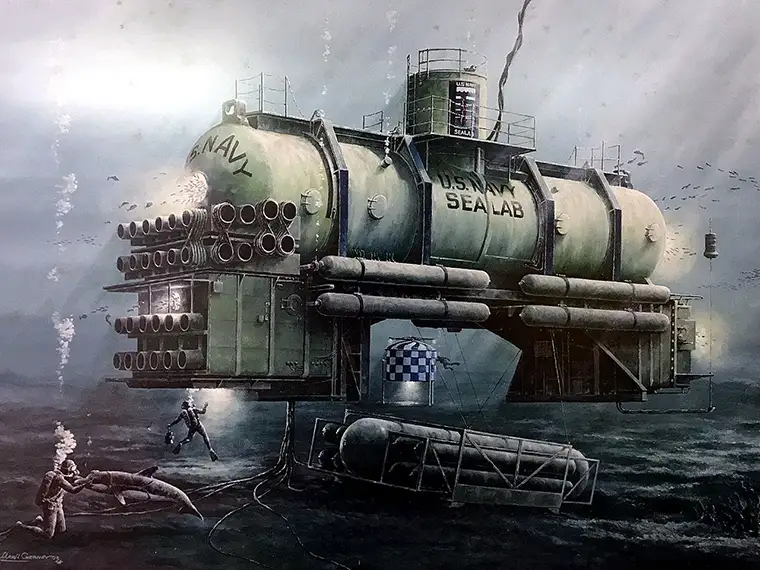

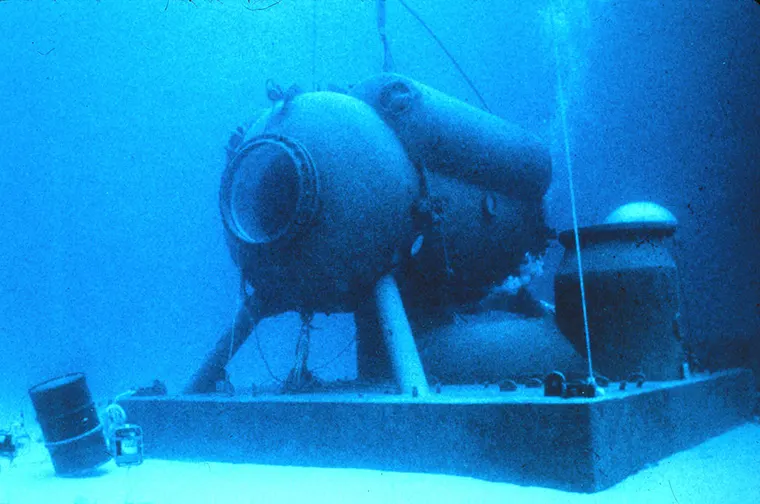

In 1964, Sealab I was deployed in 59 m/194 ft of water west of Bermuda with a crew of four divers (Robert Thompson, Lester Anderson, Robert A. Barth, and Sanders Manning).

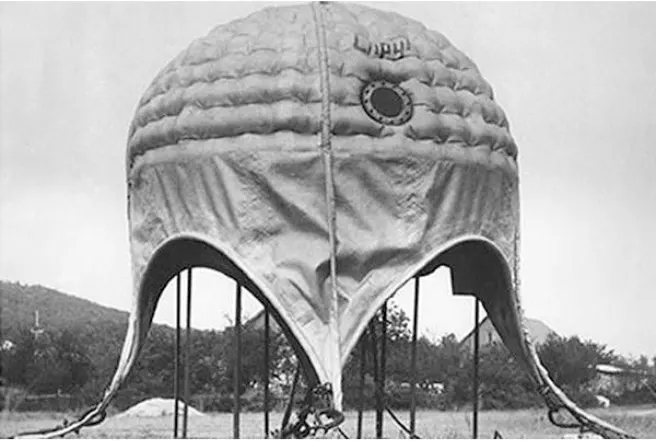

In 1964, Man In The Sea II (Submerged Portable Inflatable Dwelling, or SPID) was deployed to 126 m/413 ft with two divers, Robert Sténuit and Jon Lindburgh (son of aviator Charles Lindburgh), transferring to and from her via the Link Chamber. They spent 49 hours at depth.

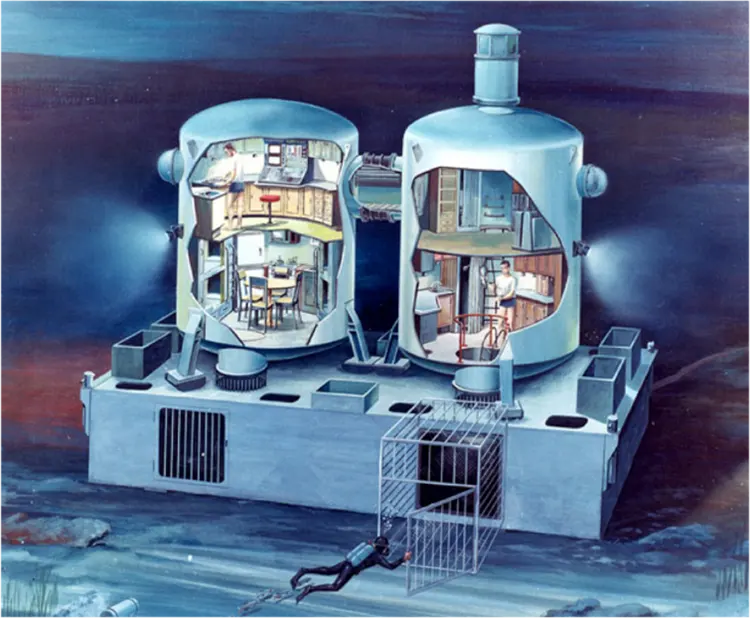

In 1965, Conshelf III was deployed in 100 m/330 ft in the Mediterranean Sea between Nice and Monaco. Six Oceanauts spent 22 days in the self-sufficient habitat working on a mock oil rig inside.

On a completely different scale, more reminiscent of our era’s cave and mine technical diving decompression habitats, Glaucus was deployed off the Breakwater Fort, Plymouth, UK in 11 m/36 ft with two recreational divers (Colin Iwin and John Heath) from Bournemouth and Poole BSAC (British Sub Aqua Club). This was the first autonomous habitat with no surface feed.

At the other end of the scale, the United States Navy deployed Sealab II in 62 m/203 ft where three separate teams of ten divers completed 15-day missions with Astronaut and Aquanaut Scott Carpenter who, through overlapping missions, spent 30 days aboard. During his mission, he established a radio link with Space Capsule Gemini in orbit, and took a congratulatory call from President Lyndon Johnson, helium-voice not withstanding.

OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP); U.S. Navy – Voyage To Inner Space – Exploring the Seas With NOAA; VIRIN: nur08016

The US Navy deployed SeaLab III—a heavily modified SeaLab II structure—off La Jolla Shores near San Diego, CA to a depth 122m/400 ft in 1998. However, Aquanaut Barry Cannon tragically died shortly after the habitat was lowered to the sea floor. The program, which was already experiencing some major issues, was complicated considerably by Cannon’s tragic death and was shut down.

Between 1966 and 1984, Hydrolab conducted 180 missions between the Bahamas and the US Virgin Islands in depths of 12 to 18 m/39 to 59 ft with four-person crews—one of which included ‘Her Deepness’ Dr. Sylvia Earle.

In 1967, Sprut (Спрут) (“Kraken”) was unique—deployment under ice for research, it withstood polar conditions.

Biological Institute Helgoland (BAH 1) was deployed in 10 m/33 ft of water with two divers (Jurgen Dorschel and Gerhard Laukner) in the Baltic Sea in 1968.

In 1969, the Atlantis operation at 25 m/82 ft in Lake Cavazzo, north of Udine in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy had a 12-person crew operating “Batinauti.”

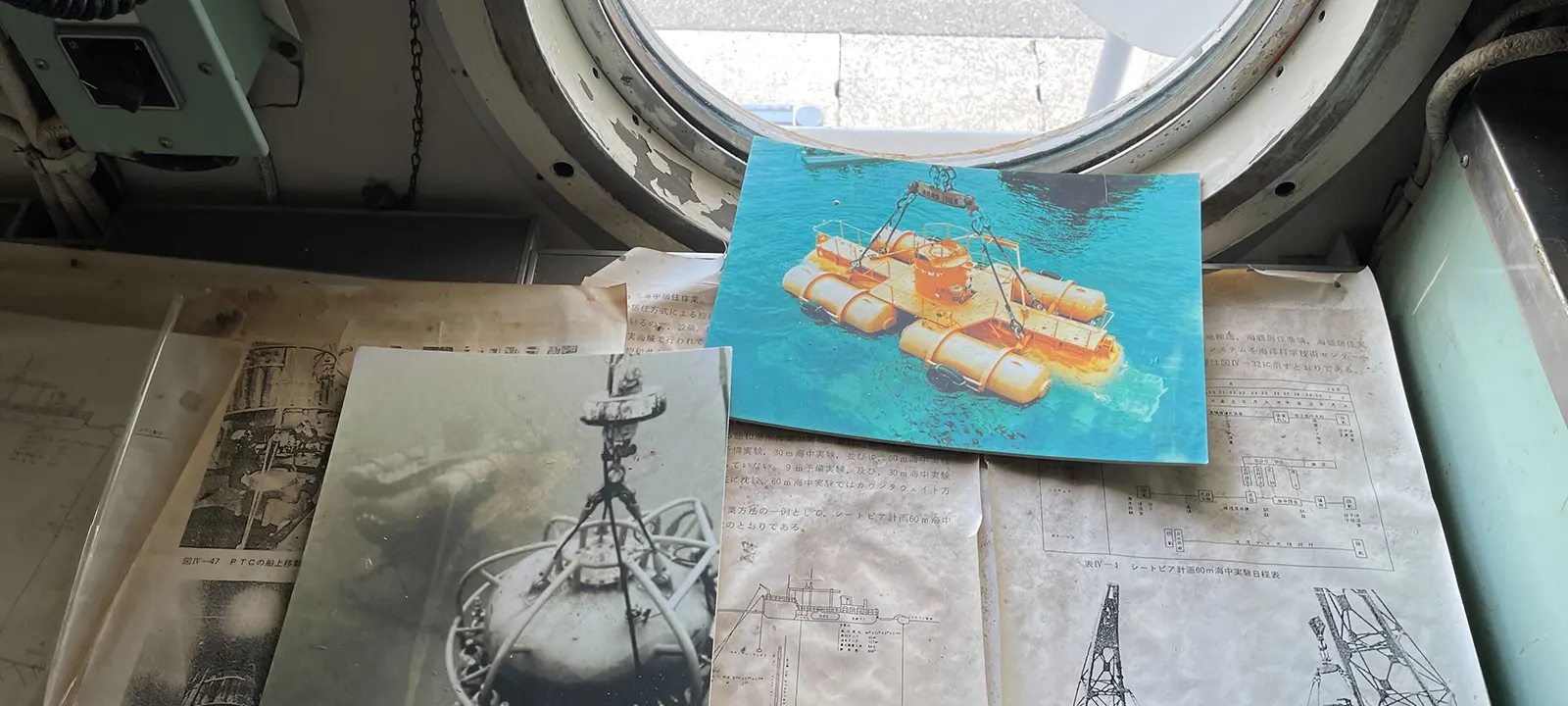

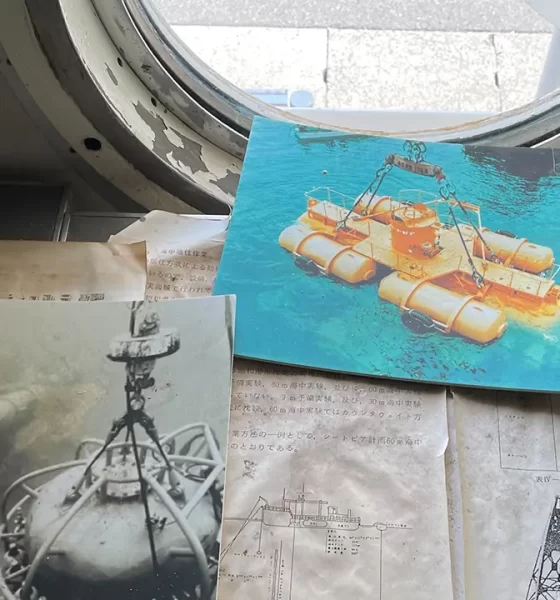

Meanwhile, Seatopia deployed in 1969 at 30 m/100 ft near Yokosuka, Japan. It had four crew for a duration of two days. Crew accessed the habitat using a closed bell via TUP.

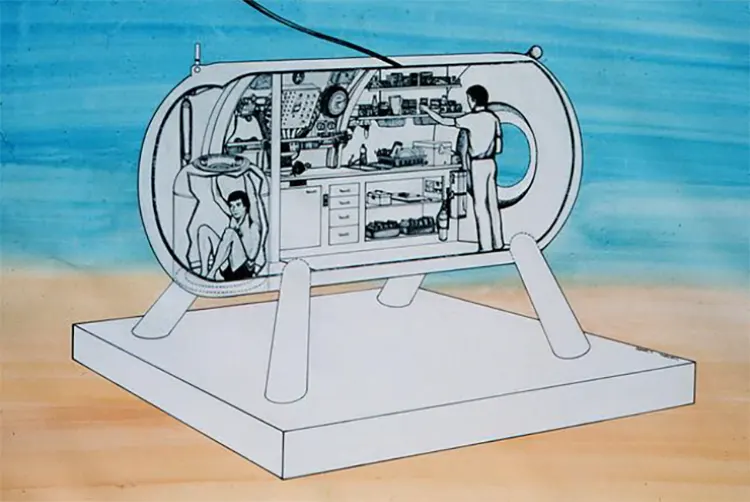

Tektite I saw Ed Clifton, Conrad Mahnken, Richard Waller, and John VanDerwalker complete a 58-day mission from 15 February to 15 April, 1969. It required 19 hours of decompression. At the time, this was a saturation diving record. In 1970, Tektite II completed ten missions from 10 to 20 days in length; one of these missions featured the first all-female Aquanaut team led by Dr. Sylvia Earle.

Meanwhile, in 1969, the Shirshov Institute of Oceanology carried out a series of oceanographic investigations using the Chernomor 2 habitat. A team of four aquanauts spent 14 days at 25 m/82 ft, and each diver conducted 2.5 to 3.5 hours of excursion diving per day. At mission end, the crew had conducted 39 hours of decompression in the underwater laboratory. Combined, all Chernomor missions totalled almost two years (760 days) of mission time.

Between 1971 and 1974, La Chalupa (now stationed in Key Largo as Jules Verne’s Undersea Lodge) was deployed between 15 and 30 m/50 to 100 ft off Puerto Rico with a four to five person crew for a 14-day mission.

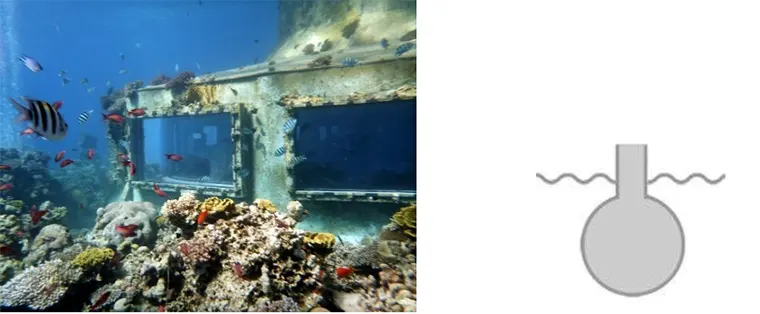

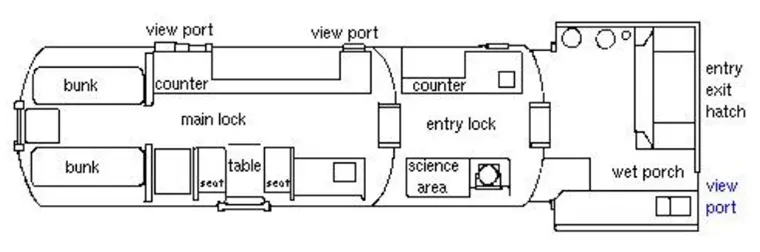

Aquarius Reef Base, located off Key Largo, Florida, at 19 m/62 ft on Conch Reef, was originally owned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and operated by the University of North Carolina-Wilmington. In 2013, Florida International University assumed operational control. The base has been used by NASA for several astronaut analogue training missions (NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations, or NEEMO).

aquaCORPS Journal (1990-1996) paid a visit to the aquanauts in Aquarius back in the mid-nineties, which was featured in the story “Aquarius Aquanautica,” by the late Dan Burton in aquaCORPS #12 SURVIVORS, OCT 1995.

In June 2014, Fabien Cousteau and his team of aquanauts lived in the Aquarius Reef Base for 31-days, dubbed Mission 31, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his grandfather’s 30-day underwater mission, Conshelf II, by living underwater one full day longer and twice as deep. They set out not only to break records, but also to conduct cutting-edge research on the dynamics of a coral reef ecosystem over an entire lunar cycle. Cousteau plans to create and launch PROTEUS™—the undersea equivalent of the International Space Station (ISS) in the not to distant future. Watch this space.

And on the lighter side, in 2015, British divewear maker Fourth Element installed its own special-application subsea habitat (SASH) at a depth of 7.6m/25 ft at TekCamp, Vobster Quay, England (Photos by Jason Brown): Fourth Element’s Subsea Swag Habitat

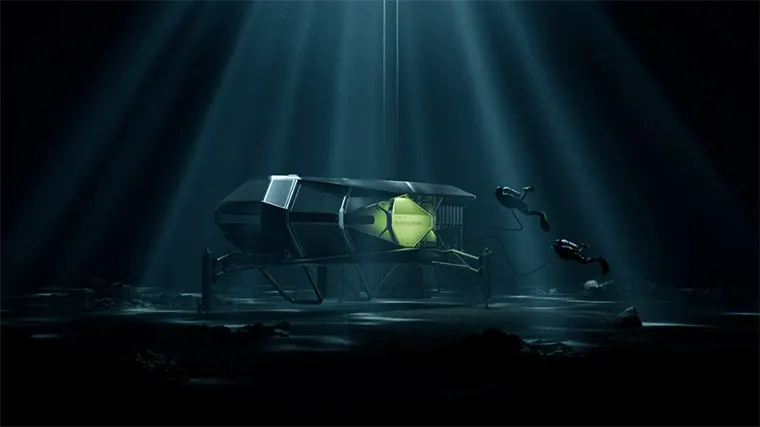

Looking to the future, DEEP is developing subsea habitats capable of extended mission durations in the 100 and 200 m/330 and 720 ft range. DEEP is working on two different, technologically advanced systems: a three-person, 100 m/330 ft exploration class habitat (Vanguard) and a six-person, 200 m/720 ft habitat (Sentinel).

DEEP habitats will be the first classed subsea habitats for human occupation, enabling humans to spend extended periods of productive time on the world’s continental shelf.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: Enabling a Permanent Human Presence Under the Oceans from 2027

DEEP: The history of subsea human habitation by Phil Short

Coastwatch: The Undersea Vision of Fabien Cousteau—Building the “ISS of the Ocean” PROTEUS™—the undersea equivalent of the International Space Station — will speed scientific discovery and may even spur medical breakthroughs. An Interview With Fabien Cousteau And Brian Helmuth.

InDEPTH: Sealab I by Ben Hellworth

InDEPTH: SEALAB III (1969): The Divers’ Story by Kevin Hardy

InDEPTH: Decompression Habitats Are Ascendent by Andy Pitkin

InDEPTH: Portable Habitats: New Technical Diving Capabilities are Well Within Reach by Michael Lombardi

BOOKS:

Amazon: Living and Working In The Sea by James W. Miller and Ian G. Koblick (1984)

Amazon: World Without Sun by Jacques Cousteau (1965)

Amazon: The Deepest Days by Robert Stenuit (1966)

Phil Short, Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (FRGS) & Fellow of the Explorers Club has been a professional Diver and Explorer for over 35 years working across most diving communities including Recreational, Technical, Scientific, Media and Commercial.

With over 6000 logged dives and 7000 dive hours, half of which on his speciality, CCR Phil has been an Instructor, Instructor Trainer and Test Diver on many CCR systems.

With a passion for Cave Exploration that led him to be lead diver on Bill Stone’s 2013 J2 Cave Expedition where Phil spent 45 days underground during a 3 month project that explored new cave 12 kilometres into the system.

For the last 3 years Phil has been Underwater Research and Training Lead at DEEP Research Labs who’s mission is to ‘Make Humans Aquatic’ by ‘Engineering Wonder’ whilst continuing his own expeditions and projects during his free time.