DCS

Diving the SOS: A Practical Discussion

The SOS meter was wildly popular in the 1970s and 80s prior to the advent and broad adoption of electronic diving computers like the EDGE. What’s more, according to avid users, like diving industry pioneer Bret Gilliam, who founded Technical Diving International (TDI) and was the former president of UWATEC, the device actually worked reliably, at least down to 55 m/180 ft. No Bend-O-Matic there! Gilliam, ever the name dropper, is positively bubbling.

Text by Bret Gilliam. Header image courtesy of Stephane Symes, other images courtesy of Bret Gilliam.

Wind the clock back five decades and re-enter an era when “square” dive profiles were the standard, and all divers used tables. Then, in 1959, Strumenti Ottoci Subacquei (SOS)—a small, Italian company led by founders Victor Aldo De Sanctis and Carlo Alinari—quietly introduced a new product. They called it a Decompression Meter or, simply, “Deco-Meter.” The device was distributed by SOS itself but also by a number of dive equipment companies.

However, the Deco-Meter got a major boost when it caught the attention of Scubapro founder Dick Bonin, a Naval officer and diver. It’s not clear exactly when Scubapro took on the actual distribution of the SOS product, but it was likely around 1967, a little less than a decade after its invention.

One of Bonin’s salesmen gave him an overview of the new SOS product while several other staff shared their practical experience with the meter. Jimmy Stewart from Scripps and engineer/designer Dick Anderson also chimed in with their own thoughts on methodology. NOAA underwater geologist Dr. Bob Dill undertook numerous deep, lengthy, repetitive dives and found that the two of us shared a common goal of making our dive exposures more efficient. He reached out to me while I was working on a US Navy project.

I was first introduced to the SOS meter in January 1971, while assigned to a Navy experimental deep diving team filming fast attack submarines in great depths. But, a lot of our standard operational and rigging protocols had us working between 18 m/60 ft and 45 m/150 ft during setups and breathing air. Our longest dive profiles resulted within the two to seven atmosphere range, and we’d already gotten input on alterations to mid-depth profiles from an experimental physiologist in Canada we were working with.

The diving medical officer on our ship was fascinated as I explained what I knew about the SOS meter as well as my conversation with NOAA diving director Dr. Morgan Wells—my first discussion about the concept of “multi-level” dive profiles—a radical departure from square table models and calculations of inert gas uptake and off-gassing. Dr. Wells had been quite interested in explaining multi-level profile theory to my Naval team in more detail to show how such a calculative departure from the norm could make us more efficient and dive within an improved margin of safety.

Almost every professional diver I knew had embraced the SOS meter and used it exclusively. Virtually every filmmaker and photographer used the SOS meter since it gave them so much more time underwater.

What Works Works

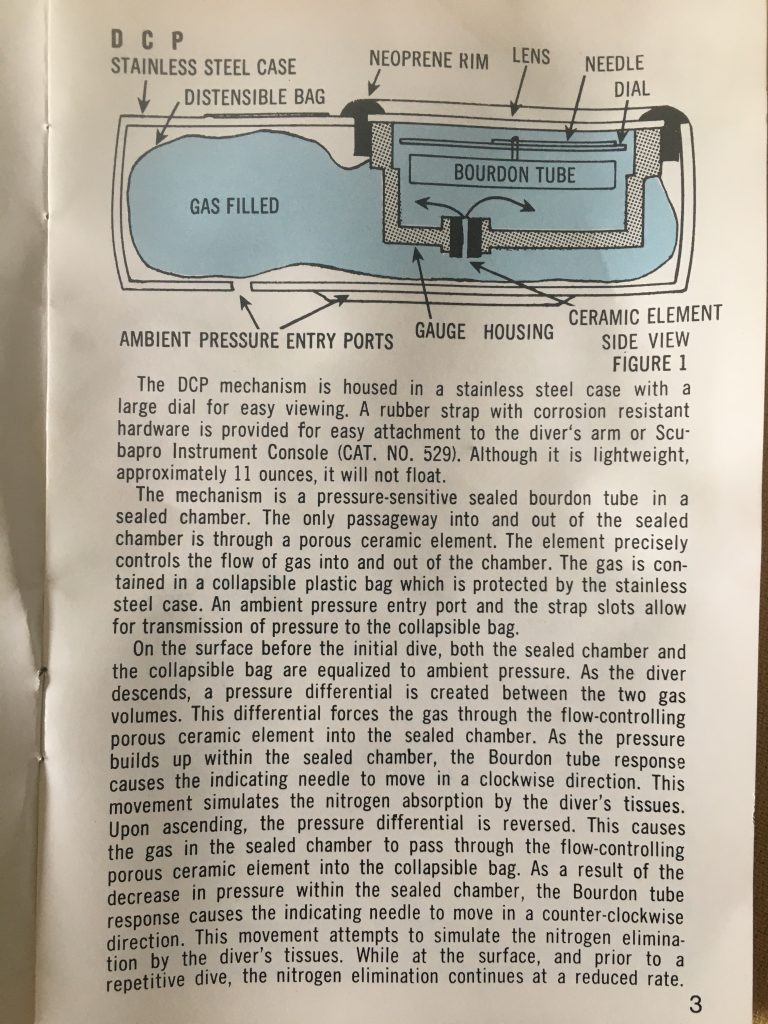

The device was incredibly simple. It was a waterproof deformable flexible chamber with a semi-porous ceramic flow pathway (Bourdon tube) that channeled the pressure through the analog needle indicator to give a display of remaining no-decompression time (or required deco, if applicable). It sounds more complicated than it is.

The mystery of the device was how the inventors were able to come up with a ceramic porous element that, incredibly, was seemingly able to match the flow rate of inert gas loading and outgassing from the diver’s tissues, and display it on analog display. From an engineering standpoint, to stumble on such a methodology so fundamentally and foundationally accurate with the barest minimum of decompression models was a physiological breakthrough of the first order.

This was not anything that Haldane saw coming.

Legendary diving physiologist, Dr. RW “Bill” Hamilton, summed it all up with his precept for decompression tools, “What works is what works.” Bill had studied, led the development of, and created so many decompression models, but the SOS device was unique, with no timing device, no depth gauge, no bottom time display—only an analog needle indicating the diving profile status. Bill used to laugh and say, “There’s no explanation for the SOS meter. It shouldn’t work because it’s based on unknown models. But, somehow it does work… nearly perfectly down to about 55 m/180 ft. And I’ve never seen a case of DCS [decompression sickness] by divers using the SOS meter. It’s kind of crazy.”

It has made for some interesting discussions over the years.

Dive tables and square profiles were slowly falling out of favor by many professional divers and numerous sport divers as well. Divers embraced the new SOS device and multi-level diving as an alternative—and safer—approach.

This was over fifty years ago, and many divers had an SOS meter if they worked in the military, commercial, scientific diving communities or with filmmaking, and underwater photography, for example on Hollywood movies, and on documentaries. And so did serious sport divers. The SOS meter was the great liberator for so many divers, since it gave them more freedom and variables.

But How Did It Work?

Since it was an analog instrument with a manual movable needle to indicate allowable no-deco or required deco, there were no batteries required. The only maintenance required was rinsing with fresh water after dives.

The lower left side of the meter contained the needle—the “blue zone” indicated no inert gas exposure. Once the dive was initiated, the analog needle traveled across the no decompression zone that spelled out SURFACE. If the needle remained within the SURFACE zone, you could immediately surface with no decompression. It was very common for divers to say, “I’m on the C,” or “Are you on the E?”

If you went into the red zone beginning with the “10 Ft.” display, you were going to be there for quite awhile. Probably a good thirty minutes or so. If you hit a “20 Ft.” stop, you were going to be there for about a month or so. And you better have a backup breathing source.

The concept of multi-level dive profiles was an extraordinary enticement to longer periods with no deco obligations. But, a lot of divers still had a hard time getting their heads around the theory and wrestled with understanding the nuance of such deco models.

It was exactly this type of misunderstanding that led some divers to be critical of the SOS meter and call it the “Bend-O-Matic.” Nothing could have been further from reality. The SOS meter had certain ranges that needed to be carefully observed to remain within no-deco limits. But, if used correctly, the SOS device had an amazing safety record. In fact, of the tens of thousands of divers using the meter, none of us were aware of a single case of decompression sickness (DCS) as long as the meters were used within their design range. That’s phenomenal.

In 1971, I was one of the diving supervisors on a commercial diving project with 126 divers doing 10-12 dives a day in depth ranges between 15 m/50 ft – 43 m/140 ft. Every aspect of the dives was controlled by the SOS meter. This went on for over two months with a perfect safety record.

When we were filming the movie “The Deep” in 1976, the entire cast (including Robert Shaw, Jackie Bissett, and Nick Nolte), Al Giddings, Stan Waterman, location crew, technicians, and divers all controlled their exposures with the SOS meter. It made everything more efficient. The same was true for countless movie, television, and documentary projects—all done on the SOS meter.

The same was true for plenty of explorations, photo shoots, and sport dives. Every diver I knew used the SOS meter with success.

Evolution Was Coming

Though the adoption of the first electronic dive computers, including Orca Industries’ EDGE, which was launched in 1982, grew throughout the 1980s, the SOS meter remained popular. But, interest waned when Dacor released the Micro-Brain in 1988, which featured a decompression algorithm designed by Dr. Albert Buhlmann, and continued to pave the way for dive computers. I later worked with Dr. Buhlmann as a consultant on later versions of the Micro-Brain’s software program.

Even though dive computers changed the sport forever by making it safer and more efficient, the SOS meter laid the foundation for the early breakthrough into modern multi-level diving profiles. That simple, amazing device incorporated the conceptual transition from tables to an alternative protocol for diving.

It was all done with the barest of technological design—yet it worked efficiently and safely.

It was not created from a mind-numbing algorithmic deco model. It was crafted from an unknown ceramic element that theoretically represented inert gas flow loading and outgassing in human tissue. When first released, it sold for $18 retail, and it was still attracting buyers over two decades later.

The SOS meter quickly went into the collectors’ cabinets and is remembered fondly as a pioneering piece of gear that launched a new technology closely followed by another revolutionary innovation: nitrox.

Time moves on, but somehow manages to get it right sometimes.

See companion story: The SOS Automatic Decompression Meter: Bendomatic or Game Changer? by Stephane Eyme

Dive Deeper:

Shearwater blog: On The EDGE by Michael Menduno

BluTime History: DECO BRAIN HANS HASS, the first dive computer by Andrea Campedelli

Dacor’s Micro-Brain Pro Plus Manual

Bret Gilliam is president of the consulting corporation OCEAN TECH, following his entrepreneurial successes in the diving and maritime industries. Bret is also a prolific writer and photographer on various subjects related to diving. He has been published in virtually every diving magazine internationally as well as National Geographic, Sports Illustrated, Outside, Time, Playboy, and many others. Author of nearly 1500 published articles, his photography has graced over 100 magazine covers, and he has been primary author, editor, or contributor to 72 books and training manuals on diving and other topics such as hyperbaric medicine, emergency treatment of diving patients in remote locations, scientific papers, maritime operations and engineering, and decompression models and algorithmic adaptations for diving computers.