Exploration

A Baltic Elegy: Åland Islands and the Wreck of Nederland

Our wandering Italian poet turned tech instructor Andrea Murdoch Alpini—or is it the other way around?— weaves a tale of a return voyage to the wreck of the river barge Nederland near the Åland Islands in the Baltic Sea. He’s there to gather clues to help him reconstruct the lyrical story of the riverboat that sank more than a century ago, and he shares the adventure on video. Cosa deve fare un sub naufrago?

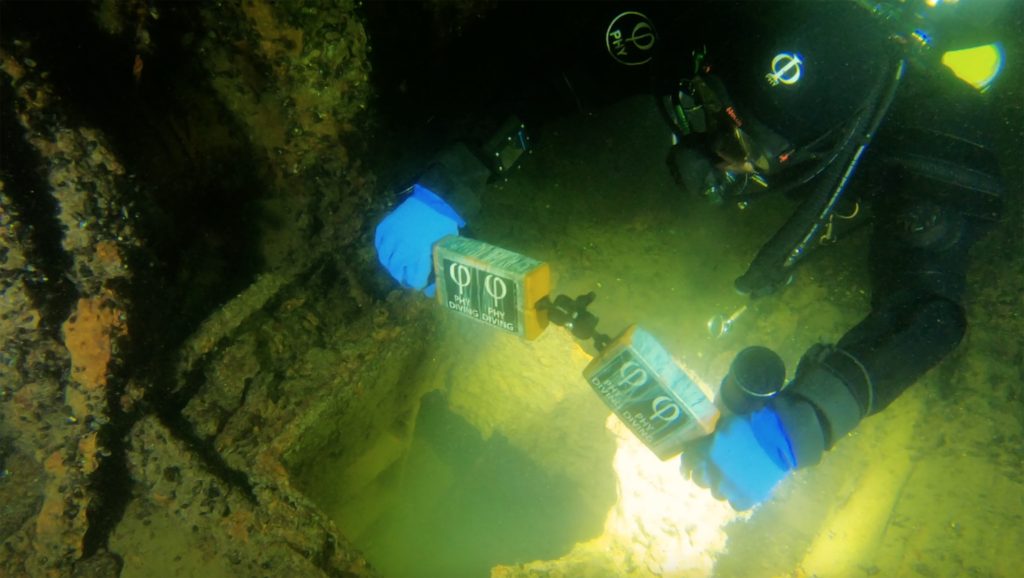

Text, video and photos: Andrea Murdock Alpini. Translation: Marianna Morè. Header Image: Flavio Cavalli lighting the starboard side of the Nederland’s wreck

To read this story in Italian, please click here: Un’elegia Baltica: le isole Åland e il relitto di “Nederland”

I believed that it had been a dozen years since my last trip to the Baltic Sea. But, when I count them, I realize just how many years have passed—more than a handful.

It was the summer fourteen years ago. Back then, as an architecture student, I organized a trip to Denmark and Sweden in search of those Scandinavian compositions that, due to their intertwinement with the landscape, seem to have come from the pencil of an ancient Greek.

I studied and researched the built environment and landscape. I never parted from my notebook, the notes I prepared for my travels, but above all my reflex camera. I voraciously took black and white, 400 ASA photographs, and sometimes I would shoot at 600 or even 800 ASA. I liked to see the film grain once the photo was printed. I never appreciated smooth surfaces, environments, or people—I always preferred the roughness of the world.

A few months ago, I left Stockholm, Sweden. There, again, the ship awaited me. This time, it would lead me to Mariehamn, the largest city in the Åland islands. When I disembarked on the Finnish islands, my long-awaited return to the Baltic Sea would finally be realized. I left almost fifteen years ago, and since then I have never forgotten it.

This time it wouldn’t be enough to just tip my toes into the water—I wanted to dive as far and as deep as the wind and sea would allow. Despite autumn knocking at the door, and the timing being all wrong, it didn’t matter. I was returning as a wreck student, ready to greet the rust and mist. And I already knew that I would return again.

After all, wrecks are nothing more than graves of crews, tales of the sea, marvels of engineering and naval manufacturing preserved by the sea.

As I reached the boarding site of the Viking, the ship that would bring me to the Åland Islands, the sky became clearer. The sun rose and the light dissolved the shadows, but the temperature remained the same. Once on board, I climbed to the tenth deck—called the Sun Deck—and a vista, looking even moodier than usual, stared back at me. The sky was black, and in the distance, layers of clouds reflected their mood on the canals of Stockholm.

At 7:45 am, the ropes slid on the bitts (paired wooden posts). The Viking casted off the moorings: navigation began.

Two and a half hours later, we arrived at the point where the Baltic Sea meets Lake Mälaren. The view finally opened, the horizon widened, and with it the silver surface of the sea for which everyone here has a different name.

Among us Mediterranean people, the Eastern sea bears the Greek name of Βαλτική Θάλασσα or Baltiké Thálassa. But, its ancestral people call it Ostsee in German, Östersjön in Swedish, Østersjøen by the Royals of Oslo, Itämeri in Alvar Aalto’s native Finnish, Østersøen by the Danes, and Morze Bałtyckie by the Poles.

To all these people, the Baltic is the Sea of the East. Estonians, for whom it represents the Western Sea, call it Läänemeri. The Russians call it Балтийское море, the Lithuanians Baltijos Jūra, and the Latvians—who define it not unlike their neighbors—Baltijas Jūra.

Shakespeare was right: “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” This slightly salty sea—black as tar, shallow and inhabited by osteichthyes—hides great stories of trade and tragic wrecks caused by storms or one of the thousands of emerging islands and islets.

The Baltic Sea preserves the memory of long battles, bloody Tsar revolutions, independence movements, and Russian submarines.

The Baltic is a book with endless pages yet to be written. Its depths conceal wrecks and preserve the remains of civilian or military sailors, of passengers, but also of bygone cultures informing rich national histories.

“Before the revolutionaries arrive, before the Bolsheviks arrive!”

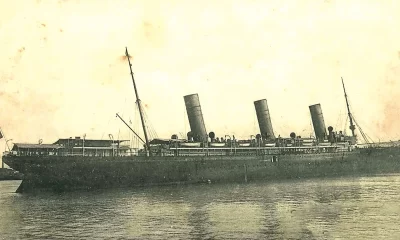

This might have been the rallying cry of the commander of the Dutch river barge that raised anchor in December 18, 1917 from Hanko, a Finnish edge of a remote Russian land. The Nederland barge had dropped its moorings with holds full of cobblestones headed to the polder kingdom, then ruled by the House of Orange-Nassau.

Even a hundred years after the barge sank off the islet of Marhällan on the Åland Islands, no one can explain why a flat-hulled, engine-less, sailing river barge had traversed the Baltic Sea for hundreds of miles to reach the land of ice. What is certain is that the crew escaped the Великая русская революция—the Bolshevik Revolution—in yet another Russian Winter, not unlike Napoleon’s invasion just over a hundred years before.

So you said”, one day in December, while a rock in the Baltic opened a leak in the hull of your barge, that was built in 1897 in Veendam in the Netherlands. As Fabrizio de Andrè sang:

“And it was winter

and like the others towards hell

you leave sad like those who have to

the wind spits snow on your face”.

Slowly, the nameless barge—now bearing the name Nederland—sank into its grave in less than 22 m/72 ft deep, nestled in between the sediment of the sea and some den of halibut or cod.

The crew survived, finding refuge on the same islet that pierced the ship’s hull: Marhällan.

Thirty hours later, the SS Mira Ship would rescue the castaways, who would tell their shipwreck story, but never the reason for their journey. No naval archive or registry contains any trace of this ship heading to the Tsars’ land in search of cobblestones.

Today, the wreck sinks under its own weight on the bottom of the Baltic Sea.

The holds barely emerge from the seabed. While crawling, you can slide under them, letting your belly rub against the century-old cobblestones squared by the frost-bitten hands of vodka-soaked laborers—the elixir aimed to fight the faint, white boredom of winter, and certainly wasn’t sipped for its taste.

The bow of the Nederland resembles its stern, like nearly all other river barges. A huge anchor keeps watch at the bow. On the starboard side, centrally-located on the main deck, hangs the mighty winch. A skylight arises where a little stairway leads below deck. I tried to penetrate there, but the mud covered everything—viscous molasses concealing all the ship’s stories, which will remain forever buried inside.

Close to the stern, the powerful rudder blade lays on the seabed. Where the hull ends, two elliptical plaques adorn the ship. The one on the starboard side bears the inscription, “Nederland,” the barge’s land of origin. The plaque on the left with the true name of the ship, leaves adventuring divers without any answer. Even if the layer of mussels twere removed, the name has disappeared, eroded by time.

The day I dived this wreck, I looked for some details that could help me reconstruct the story of this river boat. After an hour at depth, filming and searching for information about the barge, I resurfaced like my predecessors between the green, dark, and black waters of the Baltic Sea with a question: “What’s its name?”

A meter and a half-long wave obscured the lighthouse from my view, and the current pushed me away from the semi-emerging rock that births voluptuous waves of white foam. Botticelli would have painted a different Venus if he had been here, I am sure.

The Baltic is cathartic: “You want it darker / We kill the flame,” sang Leonard Cohen.🎶🎶

Yet again, I’m leaving, already feeling the need to return.

My work on this wreck is not finished yet. I have to come back; at this point it is no longer a choice, but a necessity. I will come back and tell stories of other ships and other crews, of their travels and hopes that ended at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. The separation is always a delicate moment. You have to leave, or you want to leave, but when you ruminate upon your decision, a veil of melancholy returns what had been. Intoned Cohen:

“Now so long, Mariehamn, it’s time that we began…”

In these Canadian assonances, I find the right words to describe my departure from the Finnish but Swedish-speaking islands. Tomorrow will be boarding time among the waves of goodbye:

“Here comes the morning boat / Here comes the evening flight / There goes Mariehamn now / To wave goodbye again.”

Dive Deeper

Other InDepth articles by Andrea Murdoch Alpini:

InDepth: The Man Who Immortalized The Wreck of the Andrea Doria

InDepth: No Direction Home: A Slovenia Cave Diving Adventure

InDepth: My Love Affair with the MV Viminale, the Italian Titanic

InDepth: Isverna Cave, Diving An Underground Dacia

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and CMAS technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor based in Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming, and writing. He holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. Andrea is also the founder of Phy Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching open circuit scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophy of wreck and cave diving. Recently he published his first book entitled, Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti.