Exploration

Diving the Britannic- A Personal Account

To celebrate GUE’s 20th anniversary, as well as the 20th anniversary of Quest—its membership magazine—we republished GUE founder & president Jarrod Jablonski’s account of their 1999 Britannic expedition. The story originally ran in GUE’s new magazine dirQUEST Vol. 1 #2 Winter/Spring 2000. There’s also a seven-minute trailer about the expedition.

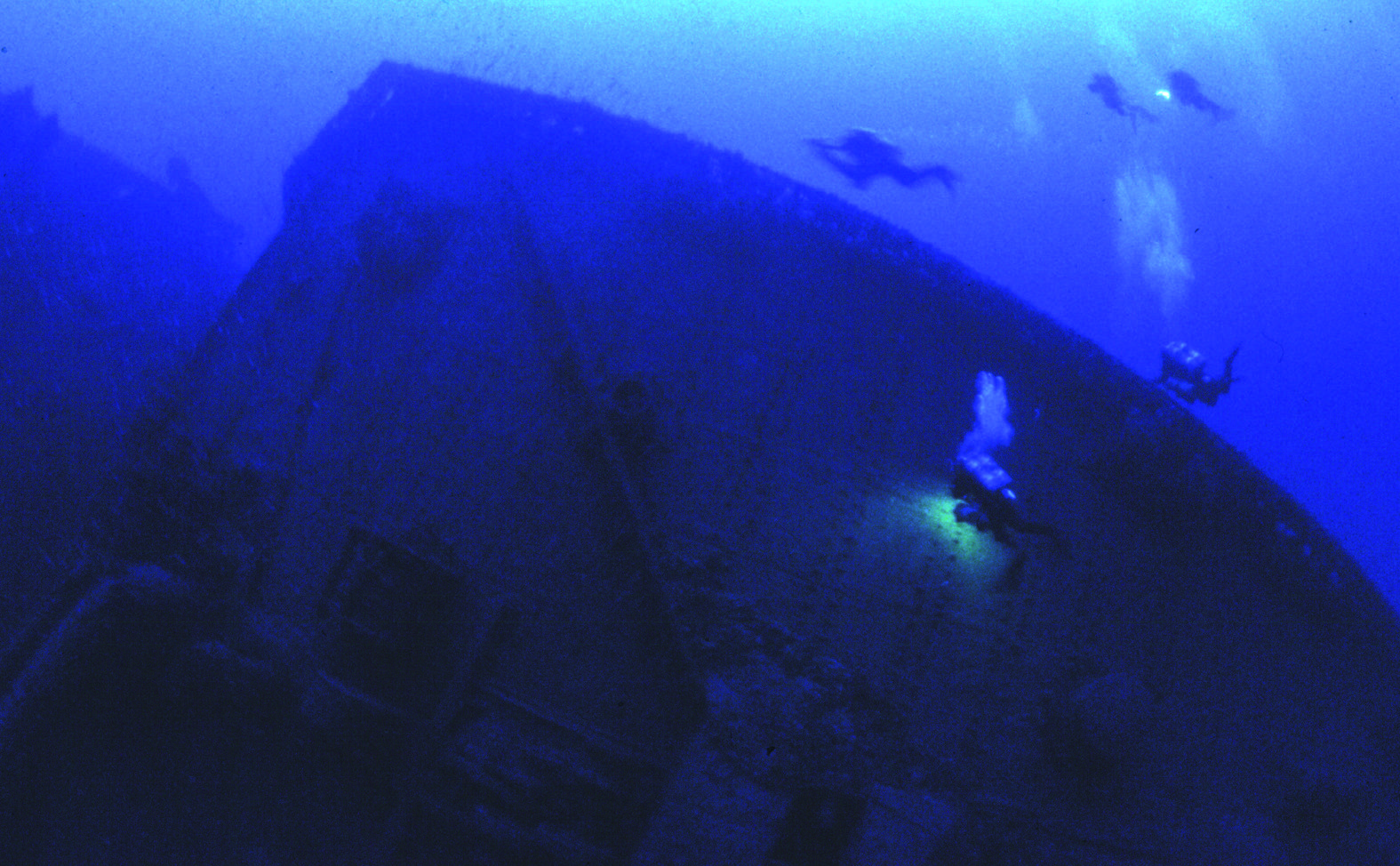

Story by Jarrod Jablonski with intro by Michael Menduno. Header photo from the GUE archives: Divers on the Britannic during the 1999 project.

In 1999, as the fledgling Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) was still finalizing its non-profit status, founder Jarrod Jablonski and team set off on their first big documentation project to document the shipwreck of the HMHS Britannic, the world’s largest passenger liner. It was the third “technical diving” expedition on the Britannic following Kevin Gurr’s 1997 expedition which included Aussie explorers Kevin Mirja Denlay, Nick Hope’s 1998 expedition with British explorer Leigh Bishop (not counting Jacques Cousteau’s 1976 expedition).

Now to celebrate the end of GUE’s 20th anniversary, and its membership magazine Quest’s 20th anniversary, we are re-publishing Jablonski’s article about the project that ran in dirQUEST Vol 1 #2 Winter/Spring 2000 (The name was changed to Quest in 2004). In addition, we offer a seven-minute trailer about the expedition.

GUE was created to meet the needs of divers who wanted to explore and conserve the underwater world. The Britannic project in 1999 put the team of divers led by Jarrod Jablonski, Todd Kincaid, and Richard Lundgren and GUE standards, procedures and skills to the test.

Now 20 years later, GUE has grown to over 90 countries with thousands of divers who are helping to enact the vision of the organization. Meanwhile, Quest has released 20 quarterly volumes of the membership magazine highlighting diving research, conservation efforts, and exploration projects.

The text below originally ran in GUE’s Quest Maganize in the spring of 2000.

Diving the Britannic- A Personal Account

By Jarrod Jablonski

Generating a level of fascination that borders on obsession, the sinking of the Titanic has captured the imagination and sentiment of millions of people around the world. The feverish interest in the Titanic, stands in stark contrast to the nearly unknown fate of her sister ship, HMS Britannic. One of three ships designed for the White Star Line to be the most opulent liners ever built the Britannic was instead fated to become the worlds largest passenger shipwreck. The two ships join a list of tragedies that seem to assert the relative frailty of human endeavors.

The mystery that surrounds the Britannic’s sinking is filled with even greater ambiguity than that of the Titanic. The Titanic‘s sinking was initiated by a collision with an iceberg. We can only speculate as to the Britannic’s assailant. After having gone down in just over two hours, the Titanic‘s revolutionary design was judged inadequate while the Britannic was still in dry-dock. The ship’s owners ordered an expensive array of improvements fitted to Britannic structure in order to avoid another Titanic catastrophe. In spite of the modifications, the Britannic sank in a mere 55 minutes on the morning of November 21, 1916. The elusiveness of Britannic’s sinking and her beautiful resting spot are certainly enough to entice any curious soul, but her record size and challenging location were all but irresistible for our group of inquisitive explorers. The allure of adventure was all that was needed to initiate the nearly year-long planning that would become GUE’s Britannic 99 Project.

Logistically speaking, the Britannic provides several interesting obstacles to staging an exploration project. The wreck rests at the bottom of the Kea Channel, a busy shipping lane just south of Athens, Greece. The southern Attica peninsula and northern Cycladic Islands lack any substantial support for diving operations. Certainly, 400-foot depths, unpredictably raging currents, capricious storms, powerful winds, and the 2,000+ mile journey did nothing to simplify the diving logistics. Because almost all of our equipment had to be shipped to Greece, preparations began several weeks before the start of the first dive when roughly 4,000 pounds of gear began its long journey to the lonely island of Kea.

Due to the great abundance of Greek antiquities (and the potential for looting), the government has historically limited access to diving to a few restricted zones in touristed areas. To stage a multi-week tri mix exploration, GUE had to build an on-site facility capable of supporting up to a dozen gas divers a day.

Team members arrived on Kea on August 18, while two transport trucks, with over three tons of gear, compressors and gas cylinders, followed close behind. Given the strict time limitations of the diving project, the equipment had to be assembled and rested in a timely fashion. The GUE team worked diligently to make the extensive preparations required to safely access the Britannic.

Preparing to Dive the Britannic

In 1975, underwater explorer Jacques Cousteau located the Britannic in 400 feet of water. Global Underwater Explorers is one of only three organizations to visit the Britannic since its discovery by Cousteau. Because it is considered a war grave by the British government, diving is strictly regulated, with access to the wreck granted no more than once a year. Although accurate GPS readings on the wreck are scarce, the Britannic’s 900-foot structure is readily identifiable with a depth sounder and locating the structure is relatively simple — especially with the capable assistance of the local Greek community.

After locating the Britannic, the advance team of Andrew Georgirsis, Steve Berman and Richard Lundgren attached a thin lead for the upline on their first shot at the wreck. As soon as the team’s lift bag broke the surface, the second team of Jarrod Jablonski, Todd Kincaid and Ted Cole departed to secure a one-inch upline and lift bag to the surface. The line was secured about a hundred feet up from the wreck’s stern.

Surface currents are typically fierce in this region and the depth of their influence can vary. Therefore, an upline was established from the bottom in stages, i.e. from 400 to 150 feet, from 150 to 70 feet and from 70 feet to the surface. This system allowed divers to cut individual sections and drift when absolutely necessary without compromising the stability of deeper upline stages. In addition, several chase boats worked in concert with the main support vessel to coordinate emergency drifting decompression or to wave off cargo ships approaching decompressing divers. Todd Kincaid coordinated efforts with Richard Lundgren, Johan Berggren, Bob Sherwood, and Joakim Johansson; the group worked tirelessly to ensure this system was as safe and flexible as necessary.

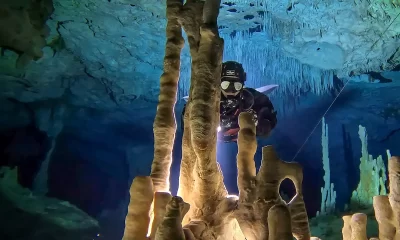

Diving the Britannic

Descending into the eerie blue water of the Aegean Sea toward the Britannic is like drifting through time. On clear days the outline of the Brirannic’s structure can be seen from as shallow as 200 feet. My first impression was one of awe — below me lay the largest passenger shipwreck in the world, rich with a unique and enigmatic history. The hazy form seems to beckon one into the depths, calling from the long, lost past.

We reached the deck, which is resting in approximately 330 feet of water and only 200 feet from the stern’s immense props. After securing the upline we continued a slow run toward the bow some 700 feet away. The Britannic lies on her starboard side leaving her port side facing up toward the distant surface about 300 feet away. The port side of this immense structure is covered in a fine, colorful growth of marine life, forming a unique blend of history and regeneration.

Traveling along the deck of the Britannic reminded me of strolling through the ancient ruins so common in Greece. The wreck is amazingly well preserved with moderate degradation and dozens of prominent features standing above her structure. Davits stand proudly above the wreck where they have rested since deploying the lifeboats that saved nearly all of her 1,000 passengers. Unfortunately, the davits and boat stands also bring to mind the 30 people who were launched from these boat stands, into the immense blades of the props.

Scootering around the wreck is a true privilege with unique bits of history adorning nearly every corner: a plaque left to commemorate Jacque Cousteau’s first dive on the Britannic, the rear telegraph for controlling the immense ship, the huge smoke funnels that once provided for her fateful journey, the huge props that propelled her along. Then there are the lamps, the coal, the cargo holds, the hallways and the ancient staircase. China cups and tiled bathrooms, spiral staircases and old light switches are but some of the many unique features to embellish our journey.

Despite all the history and beauty, the feature that most captured my imagination was the huge breach in the bow section. The damage from the rumored explosions was unusually large seemingly outstripping the possibility of a simple explosion. But were the jagged metal and puncture wound from some unidentified explosion or from her impact with the bottom some 400 feet below? Picking through the wreckage and imagining the mysterious sinking was an odd, almost mystical experience. On occasion, I actually found myself squinting at the wreckage like someone trying to make out a mysterious object just out of his or her field of view.

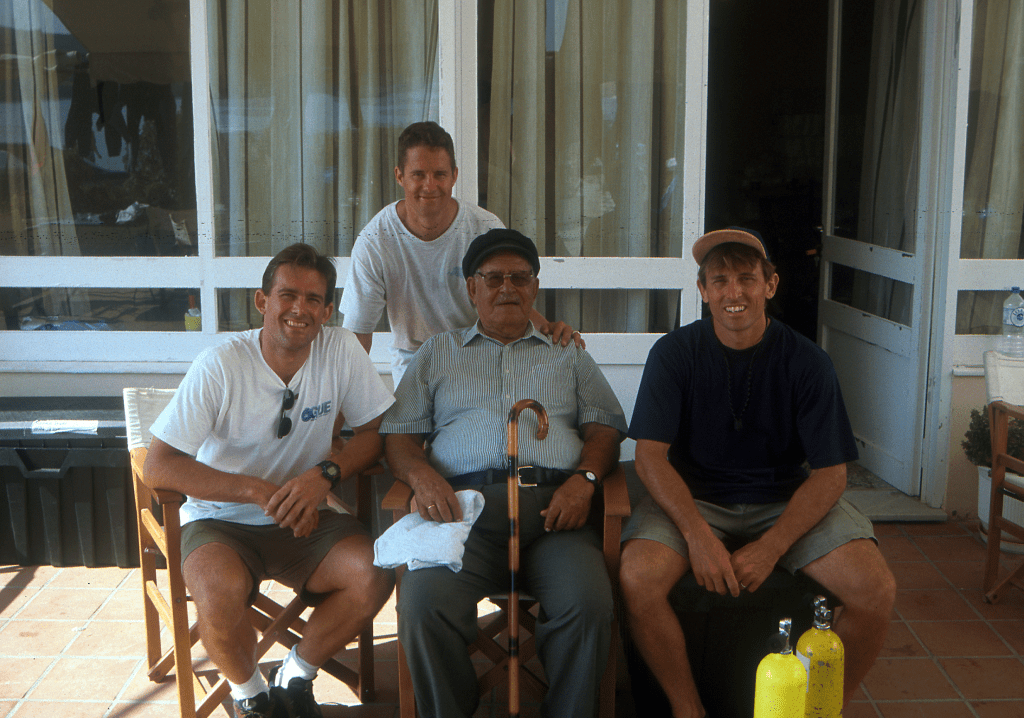

Above all of the aspects of diving the Britannic, the best part was the great sense of connection found while diving in such a unique location. Exploring the Britannic was like walking through a tunnel into the past and being able to share the experience with a group of friends and newly acquired acquaintances. Each night upon returning from a day of diving, the local residents would gather at our hotel and review the video footage, laughing and discussing the activity with childlike glee. The sense of community that emanated from these encounters left some of us feeling oddly spiritual, particularly one night when a local Greek gentleman came by and introduced himself as someone who had witnessed the sinking when he was just a small boy. We were reviewing footage from the day’s expedition — an international group of divers and local Greek citizens. I remember watching this older gentleman relive his viewing of the Britannic sinking, it all seemed to fit together: the majesty of the Britannic, the feeling of community and the connection from past to present. As I looked at this experience being etched into his face. I saw our images reflected in the glint of his aging eyes and I wondered if maybe he felt the same way.

Jarrod Jablonski is an avid explorer, researcher, author, and instructor who teaches and dives in oceans and caves around the world. Trained as a geologist, Jarrod is the founder and president of GUE and CEO of Halcyon and Extreme Exposure while remaining active in conservation, exploration, and filming projects worldwide. His explorations regularly place him in the most remote locations in the world, including numerous world record cave dives with total immersions near 30 hours. Jarrod is also an author with dozens of publications, including three books.